Computational approaches to the Arabic press of the late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean

2020-11-14

This paper originated in a presentation at Turkologentag 2018 in Bamberg, Germany, 19–21 September 2018. The computational analysis was first presented at the international workshop “Creating Spaces, Connecting Worlds: Dimensions of the Press in the Middle East and Eurasia” in Zurich, 31 October – 2 November 2019. The final version was submitted to a special issue of “Geschichte und Gesellschaft” for publication.

The current stable draft of this paper is version v0.4. To comment / review / annotate this version via hypothes.is click here. The most recent changes are available here.

High-resolution plots, data sets and other supplementary data can can be found at https://github.com/tillgrallert/s3a6afa20. If this paper gets accepted for publication, releases of this repository will be uploaded to Zenodo and get a DOI.

This essay discusses the challenges and promises of digital history—broadly understood as historiography aided by computational approaches to research questions and based on digitised sources1—for the study of historical societies of the Global South. I do so through the intellectual history of the late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean. The latter is a lose moniker for the predominantly Arabic speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean between the mountains of Anatolia in the north, Mesopotamia in the east, the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula in the south, and the Libyan desert in the west, between the mid-nineteenth century and the collapse of Ottoman rule during World War I. I explore this topic through the history of the region’s Arabic periodical press and by applying the spatial metaphor of an ideosphere as a reference to the realm of human ideas in its entirety, only some of which become manifest and thus traceable in concrete intellectual production. With ideosphere, I argue that one has to transcend individual periodicals and engage in the systematic study of the periodical press as a discursive field and at scale in order to better understand both the intellectual history of the Eastern Mediterranean at a crucial historical juncture and periodical production itself. It is important to note that most of the challenges of digital history discussed here are in no way limited to the specific case study. Instead, I present particularly pronounced variations of a theme that will ring true for all historians at a moment when the question whether something is digital or not has become increasingly meaningless and when the computational has become hegemonic as everything has already always been mediated through technology.2

Early Arabic periodicals, such as

In consequence, we still need to answer the question of what are the core nodes (authors, periodicals, other texts) in the ideosphere of the late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean and how did these networks develop over time? Answers partially depend on another set of open questions: Who authored the majority of articles that did not carry a byline? Can we confirm the common—and untested—assumption that the proprietor or editor-in-chief mentioned in a journal’s imprint authored all the anonymous texts themselves? From the underlying research question also follow larger questions with potentially severe implications for the intellectual history of the Middle East. Is the geographic bias of Cairo and Beirut justified if we look at more than the “easily” accessible handful of monthly journals? How would we need to re-write the intellectual history of the final decades of the Ottoman Empire and the Arabic nahḍa if we included the myriad of papers and their contributors from places as far as Algiers, Basra or Aleppo?

This essay computationally explores the question of authorship and references to other periodical titles and the resulting intellectual, social and geographic networks. It presents a first foray into computational approaches to these questions by adopting methods broadly summarised as distant reading, namely social network analysis and stylometry for authorship attribution. I start by confronting hyperbolic promises of mass digitisation and computational methods as a hegemonic episteme rooted in late twentieth-century, english-speaking capitalism from the margins—That is, the study of a historical multilingual society whose material heritage has been looted, destroyed and neglected; A society, whose written textual heritage resists digitisation efforts by being dependent on non-Latin scripts, which cannot reliably be extracted from facsimiles due to the limitations of available OCR technologies; A society, whose contemporary heirs between Mosul, Basra, Aleppo, Homs, the two Tripolis, Maʿān, Gaza, and Khartoum cannot draw on the vast resources in wealth and socio-technical infrastructures of the Global North (or Gulf countries).

I argue that the hegemonic digital paradigm of socio-technical infrastructures built upon English and Latin script contributes to a neo-colonial divide between the abundance of digitised cultural artefacts of the Global North and the invisibility of almost anything beyond.11 This forces scholars working on texts in non-Western languages and/or written in non-Latin scripts to engage in substantial corpus-building efforts and severely limits the scope of our computational scrutiny. I, therefore, introduce my own corpus-building project “Open Arabic Periodical Editions” (OpenArabicPE) as a framework to address the outlined challenges to mass digitisation of Arabic periodicals by combining transcriptions of a small number of early twentieth-century journals from shadow libraries12 with digital facsimiles from various vendors for the purpose of validating the former. Consequently, any corpus built with these affordances and the dependence on the work of anonymous others will not be systematically tailored to our research questions. But it is currently the only corpus of Arabic periodicals that can be subjected to computational analysis. After substantial modelling efforts, this essay presents the first results of computational analyses of bibliographic datasets of four periodicals published in Baghdad, Beirut, Cairo, and Damascus between 1906 and 1918 and digital full-text editions of three of them with a total of c. 2,65 million words. It is the first systematic attempt to empirically answer core questions for the nascent field of Arab periodical studies, which are in turn indispensable for a proper source critique if one wanted to employ these periodicals for the historiography of the late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean.

The better known and at the time widely popular Arabic journals of the late Ottoman Empire do not face the ultimate danger of their last copy being destroyed in the current onslaught from iconoclasts, institutional neglect, and wars raging through Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iraq. Yet, copies are scattered across libraries and private collections worldwide. Many collections remain unknown to scholarly communities. If catalogues exist, they are not necessarily available online and union catalogues have fallen out of fashion.13

An example shall illustrate this point. A search in WorldCat for the nine volumes of al-Muqtabas returns six different bibliographic entries, the first of which has 13 variants (called “editions” by WorldCat), pointing to 34 libraries. If one follows each entry to the holding library’s catalogue, one will find that the large majority of collections is incomplete and that collections commonly combine original volumes, reprints, microfilms, microfiches and even photo copies. This makes it almost impossible to trace discourses across journals and with the demolition and closure of libraries in the Middle East, copies are increasingly accessible to the affluent Western researcher only.14

Digitisation promises an “easy” solution to the problems of preservation and access. Access to tens if not hundreds of thousands of digitised periodical issues frequently invites the imaginaire a promised land of instantaneous one-click answers to any question one might have. The public and many scholars expect to be able to put a computer to such diverse tasks as a keyword search across the ideosphere of the early Arabic press between Morocco and Iraq since its beginnings to track semantic changes; or a social network analysis of the discursive field of authors and their texts and its changes over time. These are highly relevant questions. Unfortunately, the eager student of digitised Arabic periodicals will immediately find tools, data and skills lacking.

The first question we encounter in our attempt to track the network of authors and texts is to which extent can we submit digitised periodicals to computational analysis, or rather, what is the meaning of digitised and access? The answer is very different from periodical corpora in Western languages: from large corporate and institution-backed platforms15 to shadow libraries16 digitised in the context of Arabic and Ottoman periodicals commonly means the provision of digital facsimiles—and, sometimes, even “fakesimiles”: a digital text rendered with a layout meant to emulate the material artefact and served as an image file. While scanning and hosting millions of pages is a laudable endeavour, digital facsimiles provide access only to human readers and solely enable close-reading approaches similar to how we encounter the original artefact or microfilm copies.17

Optical character recognition (OCR), the technology to convert an image into machine-readable text, has come a long way and even hand-written text recognition (HTR) is fairly successful at least for Latin script.18 Automatic recognition of Arabic script, however, is severely lagging behind for a variety of reasons beyond the scope of this essay.19 Despite promising developments with the application of machine-learning technologies to pattern recognition,20 automatic conversion of images of early Arabic periodicals is hampered by three factors: first, all OCR technologies depend on training sets of “gold standard” transcriptions as ground truth; second, low-quality fonts, inks, and paper employed at the turn of the twentieth century will inevitably result in poor print quality and reduce the reliability of automatic transcription through variance; and third, text recognition depends on layout recognition and multi-column texts with various intersections of boilerplate, ads, etc. pose serious challenges. Consequently these texts can currently only be reliably digitised by human transcription.21 Funds for transcribing the tens to hundreds of thousands of pages of an average mundane periodical are simply not available, despite of their cultural significance and unlike what is being done with valuable manuscripts and high-brow literature.

Some platforms either ignore the problem, actively pretend it doesn’t exist, or claim to have solved it and therefore foreground search functions. Reasons range from Arabic being a marginal language in their corpus to the need to return a profit on investment through selling extremely expensive subscriptions to institutions. The advertised search functions are severely limited and often deceptive. Hathitrust, a Google-powered conglomerate of mostly American universities, is obviously dysfunctional for Arabic text if one has a look at the text layer. The commercial “Early Arabic Printed Books” (EAPB) project was developed by Cengage Gale in collaboration with the British Library and makes repeated claims of employing “[n]ewly-developed optical character recognition software (OCR) for early Arabic printed script”.22 But since they share neither text layers nor error rates or software, their claims cannot be verified. East View’s digital Arabic periodical collections (some free to use, some subscription-based) cover the middle ground. While they rely on extremely messy OCR data, which they invite their users/customers to manually improve, the interface focuses on the search box. As long as platforms show search results as highlights superimposed upon the facsimile, one can catch (the many) false positives. We will, however, never know the extent of false negatives.

The digital text of a periodical is necessary but not sufficient for many analytical queries and distant reading and it is certainly insufficient for close reading.23 The full text of a periodical would be nothing but a string of words. But periodicals unite different texts of various genres from multiple authors. These texts are commonly grouped into issues and volumes. Longer ones are frequently serialised and scattered across issues. Some of these texts are reprints from other periodicals or first printed editions of much older manuscripts. Therefore the full text has to be modelled in order to make sense of periodical for both humans and machines.24 Will Hanley’s effort of modelling the OCR’ed issues of the newspaper Egyptian Gazette (Alexandria, 1905–08) with the help of his students as part of a digital micro-history course since 2016 demonstrates how tedious this work is even with an English baseline.25

Even the provision of digitised facsimiles and raw OCR output does not mean access for all and to everything. Digital infrastructures, despite all promises towards the opposite, are rooted in the hegemony of late twentieth-century capitalism and the Global North. Most digitised periodicals are kept in opaque data silos. In the absence of provisions for interchange or interoperability in the form of application programming interfaces (APIs) or the option to bulk download data in standardised, open file formats, access to these silos is restricted to human readers and provided through proprietary web-interfaces that are commonly neither tailored to the display of Arabic material nor themselves available in Arabic.26 Such (close) reading access is further restricted by paywalls, licenses, and geo-fencing.27 Downloading content in order to circumvent ill-suited interfaces is limited to individually identifiable users. Bulk download frequently violates terms of use and most vendors try to prevent this on the technical level.

To computationally answer the above questions, however, one would need unrestricted access to truly digital editions—that is, machine-readable editions of the full text with embedded structural and semantic information and in a standardised exchange format.28

In the absence of digital editions, any meaningful computational analysis of the connections between authors, texts, and periodicals as a venue for publication and review requires access to reliable standardised bibliographic metadata as a bare minimum. Unfortunately, even this data is practically non-existent. This is due to a combination of factors: 1) ambiguity and incorrect data found in the original artefact; 2)lacking familiarity with the particularities of these artefacts among cataloguers, librarians and scholars; and 3) a software stack ill-suited for anything but Western concepts of dates and names and Western scripts.

Periodicals seem to provide no dating challenges as publication dates were conveniently recorded in a masthead. However, periodicals across the Arabic speaking late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean made use of at least four calendars. Newspapers and journals provided dates in any combination of the Ottoman fiscal, or mālī calendar and the reformed Julian calendar as well as the better known Islamic hijri and Gregorian calendars. In addition to at least three different year counts, these calendars and their users also differed in their conception of the calendric day. Most retained the old notion of a day commencing at sundown, while others adopted alla franca time with 24 equinoctial hours and a date change at midnight.29 Unfortunately supplied dates from mastheads frequently neither matched each other nor the day of the week the paper was supposedly printed on.30 How should one record this bibliographic nightmare? And which date-calendar combination should be considered the authoritative one? What if recorded publication dates were fictional to simulate a regular publication cycle and should therefore be conceived of as issue numbers that have only limited relation to an actual date?31

Any attempt to answer these questions relies on the affordances of available information systems, that is people and their skills, abstract concepts, and actual tools to record and retrieve these data points. But cataloguers, librarians and even specialists of the late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean are frequently unfamiliar with calendric systems beyond the solar Gregorian and the lunar Islamic hijrī calendars. Mālī years are frequently misread as hijrī years, which introduces a margin of error of up to two years for the last decades before World War I.32 Second, most software is unable to work with anything but Gregorian dates out of the box. Even if cataloguers were able to correctly establish the calendar used in a periodical’s masthead, the computing infrastructure would not allow them to enter this date into the digital record.33 Finally, bibliographic data is not commonly shared in a standard-compliant and machine-actionable format even when it is internally kept in structured form.34

A good example for this state of affairs is the British Library’s otherwise excellent Endangered Archives Programme (EAP), which digitised periodical holdings of the al-Aqsa Mosque’s library in Jerusalem (EAP119).35 If we look at the fourth volume of the journal al-Muqtabas available through EAP, we find that bibliographic information is solely provided in unstructured plain text.36 Publication dates are provided as Gregorian months even though the cover clearly states that al-Muqtabas follows the “Arabic”, i.e. Islamic hijrī, calendar and despite each issue reporting the publication date as hijrī month. Consequently, there is a dissonance between the facsimile and the bibliographic information. al-Muqtabas 4(1) recorded the month of Muḥarram 1327 aH in its masthead. Depending on the local observation of the moon in Damascus, the journal’s place of publication, this month began around 27 January 1909. Should al-Muqtabas 4(1) therefore be considered the January or the February issue? The cataloguers at EAP clearly thought the latter or their cataloguing software did not allow for date ranges.

Even if we had perfectly reliable digital re-mediations of the bibliographic information found in the periodical issues themselves, the vast majority of articles would remain outside our analytical scopes because publishers did not provide (meaningful) bylines—most articles in journals and newspapers from Baghdad, Beirut, Cairo or Damascus did not credit their authors. One approach is to subject all articles to stylometric analysis for authorship attribution (more on this below) but this again presupposes truly digital editions.

This state of digitised Arabic periodicals puts the onus of building a digital corpus on us—scholars of the late Ottoman ideosphere interested in leveraging computational approaches to answer pressing questions of the field. Like many others I, turned to the shadow libraries of Arabic literature, such as al-Maktaba al-Shāmila, Mishkāt, Ṣayyid al-Fawāʾid or al-Waraq. They provide access to (mostly classical) Arabic texts including transcriptions of unknown provenance, editorial principles, and quality for a small number of periodicals. These informal “editions” lack information linking the digital representation to the original artefact, namely bibliographic metadata and page breaks, which makes them almost impossible to validate and therefore employ for scholarly research.

Since we do not have the resources to proof and correct these texts, I conceived of “Open Arabic Periodical Editions” (OpenArabicPE, 2015–) as a framework for open, collaborative, and fully-referencable scholarly digital editions of early Arabic periodicals.37 OpenArabicPE addresses the above-mentioned issues of existing collections of digitised Arabic periodicals with an emphasis on accessibility, sustainability, and credibility. It builds on the simple idea of combining the virtues of immensely popular, but non-academic shadow libraries with academic and commercial scanning efforts as well as editorial expertise.

Starting with the mostly Damascene periodicals al-Muqtabas and al-Ḥaqāʾiq, we devised workflows and tools to transform digital texts (badly formatted HTML) from al-Maktaba al-Shāmila into an open, standardised file format (XML) based on the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI)’s guidelines,38 to generate bibliographic metadata, and to render a parallel display of text and facsimile in a web browser. We model the periodicals through adding structural mark-up for articles, sections, authors, and bibliographic metadata. Our schema to do so also addresses the problems outlined above and divised ways how to encode and—as far as possible—computationally normalise non-Gregorian dates and Arabic-Ottoman entity names. Finally, we link each page to facsimiles from various sources, namely EAP, HathiTrust, and Arshīf al-majallāt al-adabiyya wa-l-thaqāfiyya al-ʿarabiyya.39 The latter step, in the process of which we also make first corrections to the transcription, although trivial, is the most labour-intensive because page breaks were commonly ignored by al-Maktaba al-Shāmila’s anonymous transcribers. Each of the c.8500 pages breaks in al-Muqtabas and al-Ḥaqāʾiq needed to be manually marked by volunteers in order to link facsimiles to the digital text and thus make the text verifiable for human readers.40 So far Dimitar Dragnev, Talha Güzel, Dilan Hatun, Hans Magne Jaatun, Jakob Koppermann, Xaver Kretzschmar, Daniel Lloyd, Klara Mayer, Tobias Sick, Manzi Tanna-Händel and Layla Youssef have contributed their time to this task.

All tools and the editions are hosted on the code-sharing platform GitHub under the most permissive licenses for reading, contribution, and re-use. Retaining copyright of our own editorial contributions in the form of Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International is a reminder that the enourmous amount of, often contingent, labour embodied in digital resources need to be transparently credited. We also provide structured bibliographic metadata for every article in machine-readable formats that can easily be integrated into larger bibliographic information systems. This bibliographic data is also accessible through a constantly updated public Zotero group, which can serve as a port of entry to the editions.

With OpenArabicPE, I argue that by linking facsimiles to the digital text, every reader can validate the quality of the transcription against the original. We thus remove the greatest limitation of crowd-sourced or informal transcriptions and the main source of disciplinary contempt among historians and scholars of the Middle East. Anyone can improve the transcription as well as our modelling of a journal’s content with clear attribution of authorship and version control using .git and GitHub’s core functionality.41

The resulting corpus comprises the full text of each issue of Lughat al-ʿArab, al-Muqtabas and al-Ḥaqāʾiq until the end of World War I and a transcription of article titles and bylines for one volume of al-Ḥasnāʾ, totalling 165 full-text journal issues with some 2,65 million words (tbl. 1).42 Titles were selected based on the state of the digital editions and for their geographic ditribution. This corpus is small if compared to the vast data sets available for the Global North through Chronicling America, Trove Australia, the British Newspaper Archive etc., which gave rise to numerous distant reading projects.43 However, it is the only corpus of this material. Taken with a grain of salt, a systematic analysis of this corpus helps us test common hypotheses, challenge established narratives about the Arabic periodical press and direct the focus of further scrutiny, as I will show in the following sections after briefly introducing the constituent periodicals.

| Journal | Place | Dates | Volumes | Issues | Articles | Articles with author | in % | Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| al-Ḥaqāʾiq | Damascus | 1910–13 | 3 | 35 | 389 | 163 | 41.90 | 298090 |

| al-Ḥasnāʾ | Beirut | 1909–10 | 1 | 11 | 173 | 63 | 36.42 | |

| al-Muqtabas | Cairo, Damascus | 1906–17/18 | 9 | 96 | 2964 | 377 | 12.72 | 1981081 |

| Lughat al-ʿArab | Baghdad | 1911–14 | 3 | 34 | 939 | 152 | 16.18 | 373832 |

| total | 16 | 176 | 4465 | 755 | 2653003 |

Much less is known about the second Damascene journal in our corpus and the people behind it. al-Ḥaqāʾiq (The Facts) was a periodical of the conservative Muslim establishment, who called themselves mutadayyinūn (the very pious). A total of three volumes with 35 issues were published between 1910 and 1913 by the ʿālim (religious scholar)

The Carmelite Father

The monthly journal al-Ḥasnāʾ (The Fair Lady), published by

The quality and significance of the analysis of bibliographic data is directly dependent on the quality of the information provided by the periodicals themselves and of our mark-up in the digital editions. All relevant personal and place names in bylines and other source information must be marked up for retrieval. A core step is the necessary disambiguation of named entities through local and external authority files: “Anastās al-Karmalī”, “Buṭrus ʿAwwad”, “Sātisnā” and “The publisher of Lughat al-ʿArab”, for example, refer to the same person, “Ḥalab” and “al-Shahbāʾ” both designated the city of

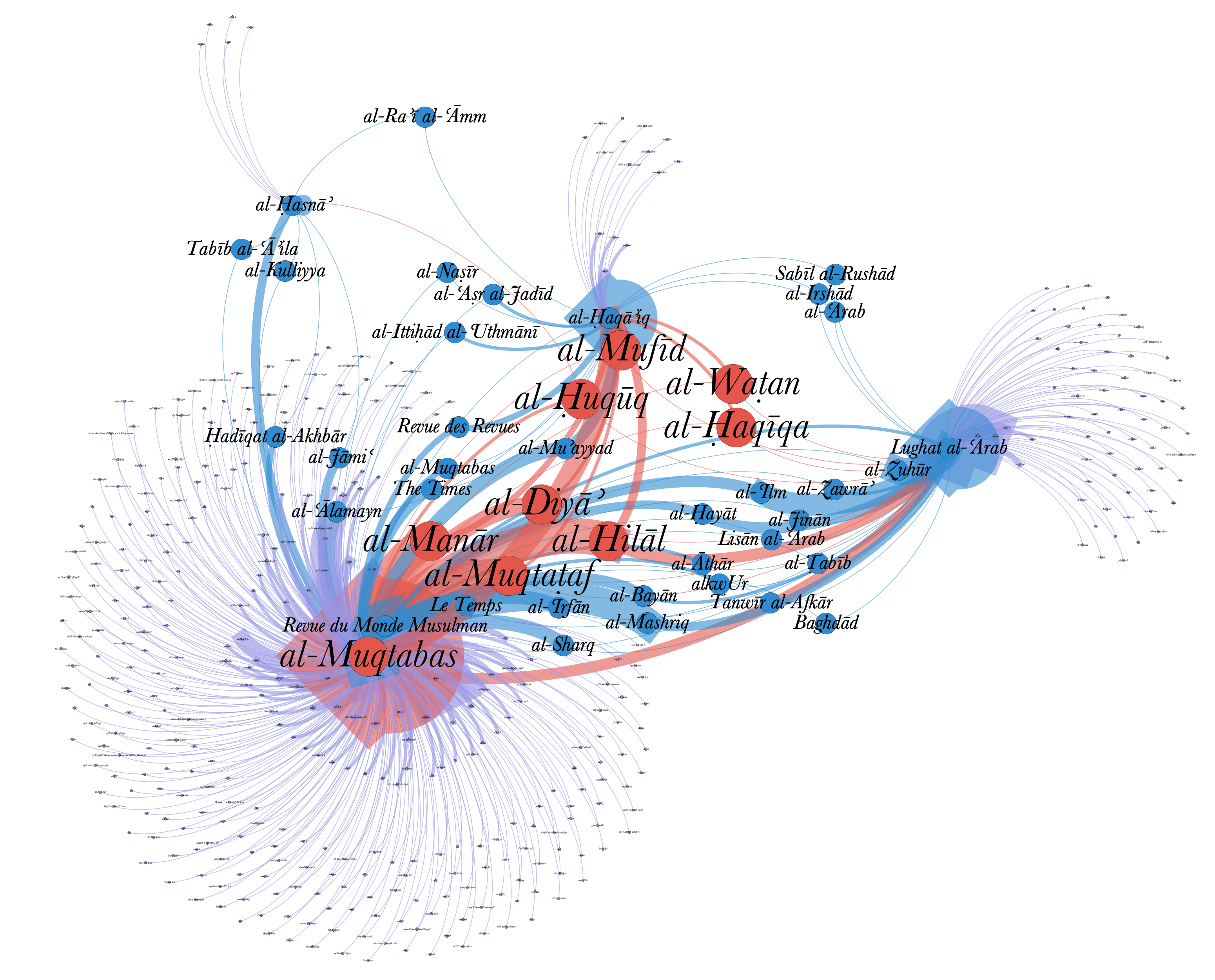

Knowing that we work with a corpus whose composition is the result of external and unknown decisions by the contributors to al-Maktaba al-Shāmila as to which periodical to transcribe, we can evaluate the performance of this corpus in representing the larger ideosphere of the periodical press in the late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean by looking at the network of referenced periodicals. Explicit references to periodicals indicated by “jarīda XYZ” or “majalla ABC” were automatically marked-up using XSLT and regular expressions and linked to local and external authority files for disambiguation and additional bibliographic information. I then counted the references to each mentioned periodical and plotted the result as a network graph. The plots feature the number of references by issue to account for the varying length of articles in each journal. Each node in the network plot (fig. 1) signifies a periodical. Edges are drawn between nodes (periodical titles) when one references the other. The thickness of the edges indicates the number of issues that reference a periodical (weight). The size and colour of nodes reflect the number of journals in our corpus that mention this periodical (in-degree).

The first observation, common to all social networks, is that only a very small number of nodes are of relative importance, as measured by in-degree (number of edges connecting to a node) and weight of the edges connecting nodes. Out of a total of 465 different periodical titles, 421 or c. 90% were referred to by only a single journal. 344 periodicals are only mentioned in a single issue and 335 in a single article. The core of the network in fig. 1 comprises only 44 periodicals mentioned by more than one journal. Only 9 of those (or 2,13% of all periodicals) were referenced by three journals in our corpus. They are: al-Manār, al-Muqtaṭaf, al-Hilāl and al-Ḍiyā from

A third observation of the larger network is that al-Muqtabas accounts for the vast majority of references to other periodicals by some orders of magnitude even after we account for al-Muqtabas having almost thrice as many issues as either al-Ḥaqāʾiq or Lughat al-ʿArab (tbl. 1). If we assume that we haven’t missed a significant number of references, then al-Muqtabas was more outward-looking and more involved in larger discourses of the day. Fourth, a closer look at the core nodes in the network reveals that all periodicals were primarily self-referential—indicated by the thickest edges connecting a journal to itself (for the purpose of this visualisation and to prevent circular edges, source and target nodes were separated). Fifth, the core nodes include number of surprises: al-Jinān was published by

Sketching a network of periodicals and the references between them is only one part in the endeavour to layout the ideosphere of the late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean. Another is the network of authors who published in these periodicals and the geographic distribution of places they wrote from. Knowing the importance of certain authors for an individual periodical is the basis for mapping the network of authors across the late Ottoman ideosphere.

The aim would be to map a network for the hundreds of journals and newspapers published between

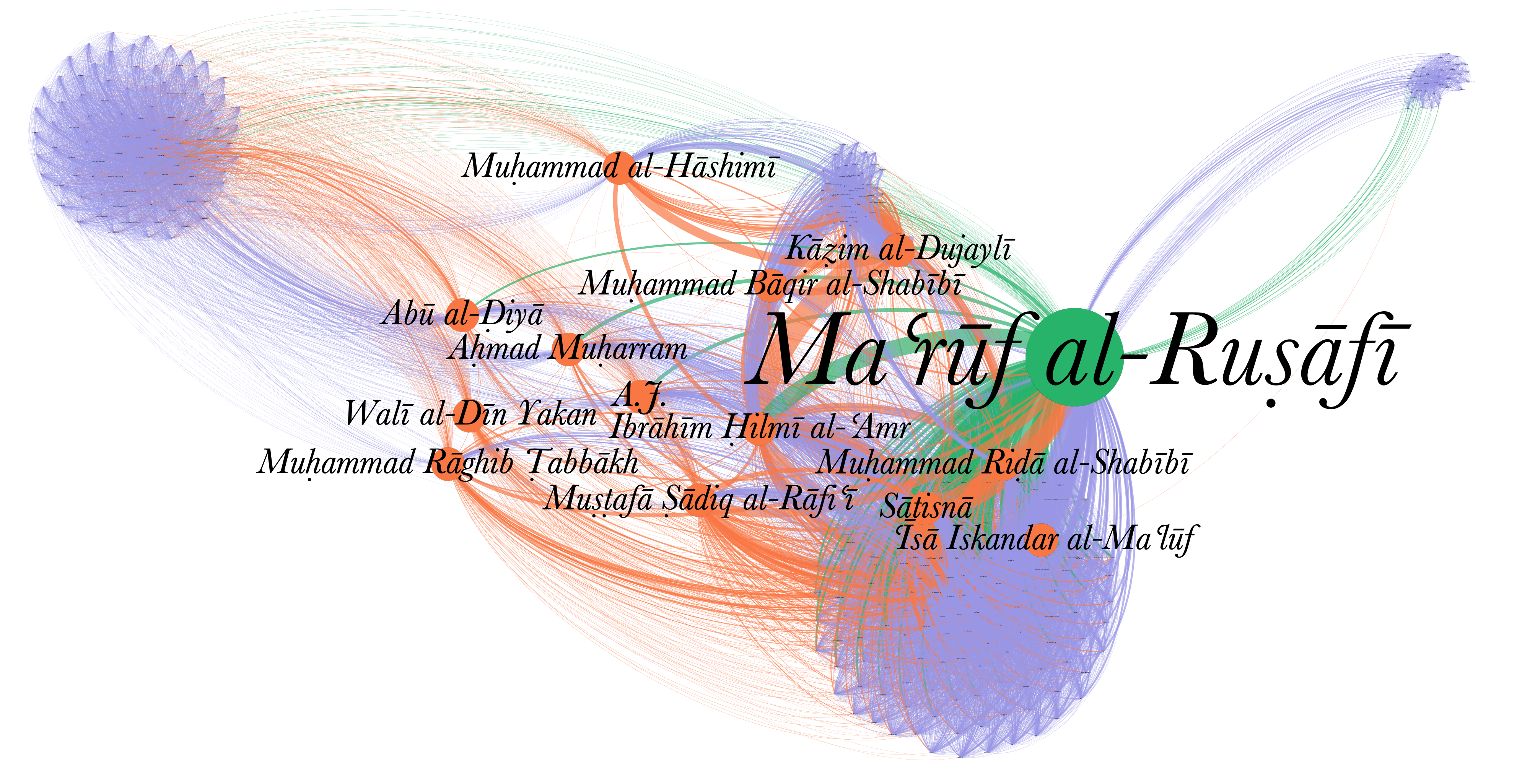

The first observation, again, is that only a very small number of nodes (14 of 319) are of relative importance as measured in degree (number of edges connecting to a node) and weight of the edges. In the network plot (fig. 2), edges were drawn between all authors who published in the same periodical. Colours and size of nodes signify the out-degree or the number of journals in our corpus in which an author had bylines. The thickness of the edges is a function of the number of articles carrying the byline of a given author. Nodes of authors who published only in a single journal form dense clusters. These are: al-Ḥaqāʾiq to the left, al-Muqtabas bottom centre, Lughat al-ʿArab top centre, and al-Ḥasnāʾ to the right.

A closer look at the central nodes of the network reveals that only one author published in all four journals:

The other 13 central nodes had bylines in only two out of four journals. Only eight of the fourteen authors can be found in international authority files, which at least means that they have not authored works catalogued in any of the contributing libraries (see tbl. 2). Those for whom we have biographic information (employing more traditional close reading of Arabic prosopographic literature)56 were on average in their mid-thirties during the years under investigation. There is a surprising number of Iraqis and a notable absence of Syrians from this network of two Damascene journals and one periodical from Beirut and Baghdad each. Among the eleven identifiable authors, there are six Iraqis:

In terms of education and occupations the core nodes are exemplary for the bourgeois middle-class intelligentsia of their time: many attended Ottoman state schools in addition to more traditional, religious venues of education; many knew foreign languages in addition to Arabic and Ottoman; some were trained or even taught abroad in the colonial centres of Paris and London; some served in the Ottoman bureaucracy; some were educators. There is also a significant number of poets (7) among the central nodes58 and a small number of politicians (MPs). The more prolific of them were themselves journalists who at one time or another operated their own periodical(s):

Another striking observation can be found in the proximity and overlap of clusters. Two of the journals in our corpus, al-Muqtabas and al-Ḥaqāʾiq, were predominantly published in the same city but there is only very limited overlap. Their clusters are only losely connected by a handful of people who have only one or two bylines in each journal. The ties between

The work on compiling the biographies of all 319 currently identifiable contributors is far from being done, but after looking at the most productive authors for each journal, we can identify certain trends in the author populations and their geographic distributions. For the purpose of this essay, I will contrast al-Muqtabas and al-Ḥaqāʾiq, the two Damascene periodicals in our corpus.

Only 50 authors published more than one article in al-Muqtabas. Two of the five most prolific authors with more than ten bylines to their names wrote from

The four men out of the five, for whom we can find biographical records, are in many aspects exemplary of the modernising late Ottoman Empire and the Middle East: Coming from a plurality of religious and social backgrounds—Greek Orthodox, Catholic and Sunnī Muslim, priest and leading Salafi thinker of the second generation, part-time officials, of simple means and members of the old elites—they belonged to the same generation (born between the mid-1860s and mid-1870s) and worked as journalists, teachers, and occasionally politicians. All of them were highly mobile and well-travelled and had good command of local as well as foreign languages—to the extent that some of them published literary translations. The fifth man is not less exemplary, even though his story seems to be rather uncommon among journalists:

The geographic distribution and relative frequencies of locations mentioned in bylines conveys the same image as the network of referenced periodicals and the brief comments on the most prolific authors’ biographies: al-Muqtabas was a publication of at least regional importance. It reached well beyond Greater Syria to Egypt, Iraq and even America, turning the famous proverb “Cairo writes, Beirut publishes and Baghdad reads” upside down with Baghdad well ahead of even Damascus.63

The picture is different for al-Ḥaqāʾiq (tbl. 4), which was repeatedly in conflict with al-Muqtabas over the latter’s supposed moral laxity. Its most prolific contributors were Damascene Sunni religious scholars from notable families, many of whom were at least one generation older than its opponents (the average year of birth for al-Ḥaqāʾiq is 1837 and 1869 for al-Muqtabas). Among them are

A map of the relative frequency of locations mentioned in bylines confirms the brief overview of the authors’ biographies—al-Ḥaqā’iq was a parochial paper with a focus on local issues. Its geographic network was mainly restricted to Damascus itself and the cities of the Syrian hinterland. Similarly distinctly regional distributions of authorship can be established for one of the two remain periodicals in our corpus: al-Ḥasnāʾ. Lughat al-ʿArab, on the other hand, only rarely provided locations in bylines (26 of 939 articles), which doesn’t allow for meaningful observations.64

It is worth going back to the bibliographic data, its shortcomings and the resulting consequences for our analysis. We are particularly concerned with the number of articles that carried bylines or otherwise easily identifiable authorship information.65 All journals in our corpus, like any other periodical at the time I have seen, published only limited authorship information. About 42% of all articles in al-Ḥaqāʾiq carried authorship information (tbl. 1). Second is al-Ḥasnāʾ with 36% , followed by Lughat al-ʿArab with 16% and al-Muqtabas with not even 13% . In consequence and due to the heavy weight of al-Muqtabas in our corpus, we can only map 16,91% of the entire network of articles by looking at explicit bibliographic information alone. More than four fifths are hidden from our view.

Surprisingly the question of authorship has not received much attention.66 The, often implicit and accepted, hypothesis is that periodical editors authored all articles for which they did not provide a meaningful byline themselves.67

This raises a number of problems and considerations. Most importantly, the hypothesis remains untested. Second, we simply do not know enough about any given periodical to even name all editors. Cover pages of journals and mastheads of newspapers had a limited vocabulary to state responsibilities for an issue, not all of which were always provided: owner or concessionary (ṣāḥib, ṣāḥib al-imtiyāz), responsible director (al-mudīr al-masʾūl) and editor-in-chief (raʾis al-taḥrīr).68 Commonly these functions converged and periodicals provided only a single name. Third, it is highly unlikely that a single person authored and edited almost the complete content of a periodical in addition to operating the whole business of publishing. Some owners-cum-editors ran more than one periodical.

On a more empirical level, we can find repeated calls from multiple periodicals on authors of anonymously submitted contributions to come forward and provide their identities to the publishers.72 In a similar vein, the newspaper al-Muqtabas rejected allegations that articles published by pseudonymous authors were indeed authored by the editors.73

(Computational) stylistics or stylometry is a common and established approach in linguistics and literary studies for authorship attribution and genre detection. It is based the observation “that authors tend to write in relatively consistent, recognizable and unique ways”, which is particularly true for an author’s choice of words.74 In the context of stylometry, “style” commonly means a frequency count of words used in a given text.75 Stylometry then computes degrees of similarity between texts, called distance measure, through comparing multivariant frequency lists of textual features. The important catch is that stylometry is a comparative method. In order to establish similarities one has to have access to a significant corpus of digital texts by authors likely to be found among the unattributed texts. If we only compare every article in our periodical corpus to every other article in the same corpus, we cannot possibly identify any author not yet named in a byline. Instead, the best we could hope for would be to establish groups of texts that have a certain likelihood of having been authored by the same person.

The present essay is the first foray into stylometric authorship attribution for Arabic periodicals. Czygan’s work is the only attempt at stylometric authorship attribution for Ottoman periodicals I have come across, but, after developing a set of style markers for individual editors-cum-authors, the author did not apply them for actual authorship attribution.76

There is some debate as to which style-markers and distance measure should be considered for authorship attribution, but I settled on Most Frequent Words (MFW) and Burrows’ Delta.77 Texts were not pre-processed by morphologising or lemmatizing, as this would reduce the authorship signal to the vocabulary used. Similarly, function words, which, by definition, are the most frequent words, were not removed. Their frequency is independent of a text’s topic and it is unlikely that an author can consciously control this frequency.78

Because the number of MFW has a significant impact on the results,Eder suggested to use consensus networks in order to separate signal and noise. To this end, one computes the nearest neighbour as well as the first two runners-up for a sequence of MFW (e.g. from 100 to 1000 MFW in increments of 100) and then combines the results in a single output, which serves as a form of self-validation for the more robust signals. The results can then be visualised using network analysis.79

Finally, there is an important caveat in applying stylometry to periodicals: Eder experimentally established a threshold length of 5000 words as the minimal required length of a text for meaningful attribution. Below 5000 words, the signal was “immensely affected by random noise”.80 These findings have severe implications—most texts in our corpus are much shorter than 5000 words and even the longer ones are too short for random sampling. Nevertheless, limiting our experiments with stylometric analysis to the some fifty articles of more than 5000 words yielded promising results and shows at least three distinct signals: genre, author and translator/editor.81

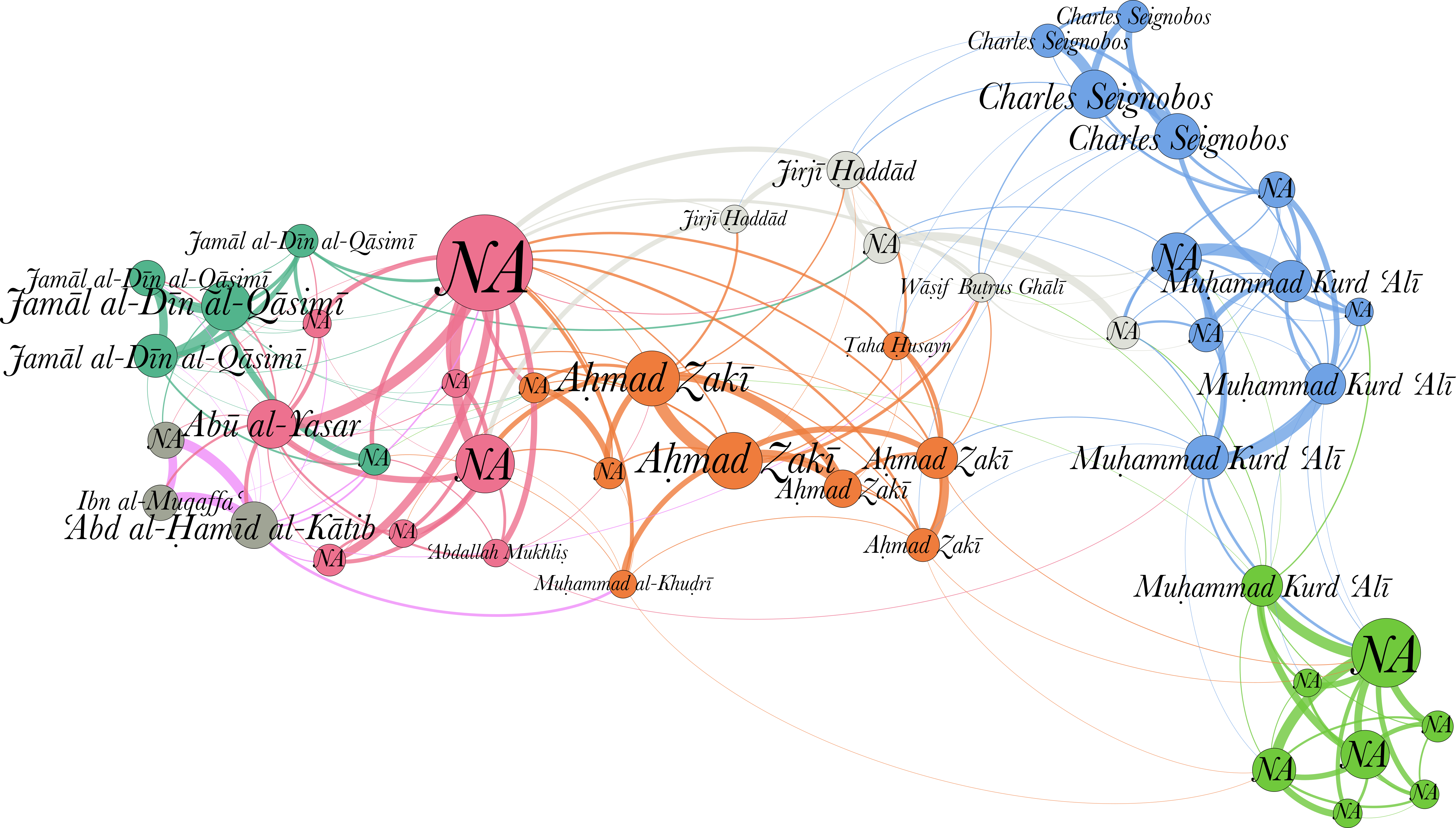

Our initial analysis of all articles of 5000 words and more using bootstrap networks for 100–1000 MFWs confirms the general applicability of stylometry to our corpus (fig. 3). Articles form clusters based on edge weight and modularity around authors, editors and translators. Thus, we find clusters of articles authored by

Furthermore, the plot also shows a strong signal of genre: the cluster of unattributed texts most likely written by

In this essay, I questioned hyperbolic promises of ubiquitous digitised knowledge from the marginal position of Middle Eastern intellectual history and by outlining the techno-infrastructural challenges faced by a “digital history” of societies outside the Global North. I showed, how a digital episteme deeply rooted in 20th-century, english-speaking capitalism requires mitigation strategies on every level of the digital workflow. These are placed on the individual scholar and involve significant investments in the making of corpora, resources and tools if we want to reap the promised fruits of the digital humanities. I also posed that one of the consequences of this episteme is a neo-colonial silencing of the material heritage of the societies in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Nevertheless, digital corpora and computational approaches are indispensable for scrutinising the periodical press as an ideosphere. I argued that one has to transcend the individual periodical and engage in a systematic study of the periodical press at scale in order to better understand both the intellectual history of the Eastern Mediterranean and periodical production itself. The case study of a corpus of four late Ottoman Arabic-speaking periodicals from the Eastern Mediterranean (al-Muqtabas, al-Ḥaqaʾiq, Lughat al-ʿArab, and al-Ḥasnāʾ) introduced and evaluated some of the mitigation strategies. After introducing my own efforts of building an open and scholarly digital corpus, I engaged in computational exploration through network analysis, mapping, and stylometry along the guiding question of what were the core nodes (authors and periodicals) in the ideoscape of the late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean?

Modelling the network of references to periodical titles, I could confirm established knowledge about the importance of certain journals over others. The Cairene journals of al-Manār, al-Muqtaṭaf and al-Hilāl were indeed central to the late Ottoman Arabic ideosphere, even though they were published outside the Ottoman Empire. A future systematic exploration of periodicals will have to digitise these and compare them to al-Muqtabas, which shows many traits of a periodical of transregional importance very different from the other journals in our corpus.

The exploration of the network of article authors, on the other hand, provided a number of surprising results that will need to be addressed in future scholarship: The noted importance of Iraqi writers over Syrians among the core nodes of the network contradicts the common narrative about the Arabic renaissance (nahḍa). A similar importance of

Any analysis of authorship and socio-intellectual networks is limited by the fact that less than one fifth of all articles carry identifiable authorship information. I, therefore, presented a first empirical analysis of the common but untested hypothesis that editors authored the four fifths of anonymous articles themselves by submitting our corpus to stylometric authorship attribution. This provided significant hints towards authors of articles longer than 5000 words. Although we cannot (yet) assign a specific name, the analysis of articles from al-Muqtabas returned one cluster of texts by an anonymous author very different from those articles that can indeed by attributed to the editor Muḥammad Kurd ʿAlī.

Arguing with Digital History working group. ‘Digital History and Argument’. White paper, 13 November 2017. https://rrchnm.org/argument-white-paper/.

Abou-Hodeib, Toufoul. A Taste for Home: The Modern Middle Class in Ottoman Beirut. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017.

Abu Harb, Qasem. ‘Digitisation of Islamic Manuscripts and Periodicals in Jerusalem and Acre’. In From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives Programme, edited by Maja Kominko, 377–415. Open Book Publishers, 2015. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.12.

Aman, Mohammed M. Arab Periodicals and Serials: A Subject Bibliography. Garland Reference Library of Social Science. New York: Garland, 1979.

Atabaki, Touraj, and Solmaz Rustămova-Tohidi. Baku Documents: Union Catalogue of Persian, Azerbaijani, Ottoman Turkish and Arabic Serials and Newspapers in the Libraries of the Republic of Azerbaijan. London: Tauris Academic Studies, 1995.

Ayalon, Ami. ‘The Arab Discovery of America in the Nineteenth Century’. Middle Eastern Studies 20, no. 4 (1984): 5–17. https://doi.org/10/b9tmbm.

———. ‘Semantics and the Modern History of Non-European Societies: Arab “Republics” as a Case Study’. The Historical Journal 28, no. 4 (1985): 821–34. https://doi.org/10/cfszw3.

———. Language and Change in the Arab Middle East the Evolution of Modern Arabic Political Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

———. ‘Sihafa: The Arab Experiment in Journalism’. Middle Eastern Studies 28, no. 2 (1992): 258–80. https://doi.org/10/fqwxp9.

———. The Press in the Arab Middle East: A History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

———. ‘Modern Texts and Their Readers in Late Ottoman Palestine’. Middle Eastern Studies 38, no. 4 (2002): 17–40. https://doi.org/10/c8sg6m.

———. ‘From Fitna to Thawra’. Studia Islamica 66, no. 66 (January 1987): 145–74. https://doi.org/10/c77s26.

———. ‘Private Publishing in the Naḥda’. International Journal of Middle East Studies 40, no. 4 (November 2008): 561–77. https://doi.org/10/d2vxjg.

Bastian, Mathieu, Sebastien Heymann, and Mathieu Jacomy. Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks, 2009. http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/09/paper/view/154.

Berry, David M, and Anders Fagerjord. Digital Humanities: Knowledge and Critique in a Digital Age. Cambridge; Malden: Polity, 2017.

Bingham, Adrian. ‘“The Digitization of Newspaper Archives: Opportunities and Challenges for Historians”’. Twentieth Century British History 21, no. 2 (June 2010): 225–31. https://doi.org/10/fsqbgx.

Brake, Laurel. ‘The Longevity of “Ephemera”: Library Editions of Nineteenth-Century Periodicals and Newspapers’. Media History 18, no. 1 (2012): 7–20. https://doi.org/10/b7x6ps.

Burrows, John. ‘“Delta”: A Measure of Stylistic Difference and a Guide to Likely Authorship’. Literary and Linguistic Computing 17, no. 3 (September 2002): 267–87. https://doi.org/10/cm2hbk.

Cioeta, Donald J. ‘Thamarāt Al-Funūn, Syria’s First Islamic Newspaper, 1875-1908’. PhD Thesis, University of Chicago, 1979.

Commins, David. Islamic Reform: Politics and Social Change in Late Ottoman Syria. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Cristianini, Nello, Thomas Lansdall-Welfare, and Gaetano Dato. ‘Large-Scale Content Analysis of Historical Newspapers in the Town of Gorizia 1873–1914’. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 51, no. 3 (26 March 2018): 139–64. https://doi.org/10/ggqm97.

Czygan, Christiane. Zur Ordnung des Staates: jungosmanische Intellektuelle und ihre Konzepte in der Zeitung Ḥürriyet (1868-1870). Berlin: Klaus Schwarz, 2012.

Dāghir, Yūsuf Aḥmad. Qāmūs al-ṣiḥāfa al-Lubnāniyya 1858-1974. Bayrūt: al-Maktaba al-Sharqiyya al-Kubrā, 1978.

Dāghir, Yūsuf Asʿad. Maṣādir al-dirāsa al-adabiyya. 2 vols. Ṣaydā: al-Maṭbaʿa al-Mukhliṣiyya, 1950.

De Jong, Fred. ‘Arabic Periodicals Published in Syria Before 1946: The Holdings of Zahiriyya Library in Damascus’. Bibliotheca Orientalis 36 (1979): 292–300.

Deny, Jean. ‘L’adoption du calendrier grégorien en Turquie’. Revue du monde musulman 43 (1921): 46–52.

Deringil, Selim. The Well-Protected Domains: Ideology and the Legitimation of Power in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1909. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 1998.

DFG-Praxisregeln ‘Digitalisierung’. Bonn: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, 2016. http://www.dfg.de/formulare/12_151/12_151_de.pdf.

Driscoll, Matthew James, and Elena Pierazzo, eds. Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories and Practices. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2016. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0095.

‘Early Arabic Printed Books from the British Library’, 16 September 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190916173504/https://p-www.gale.com/primary-sources/early-arabic-printed-books-from-the-british-library.

Eder, Maciej. ‘Does Size Matter? Authorship Attribution, Small Samples, Big Problem’. Literary and Linguistic Computing 30, no. 2 (June 2015): 167–82. https://doi.org/10/ggvhx4.

———. ‘Visualization in Stylometry: Cluster Analysis Using Networks’. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 32, no. 1 (April 2017): 50–64. https://doi.org/10/gfspxg.

Eder, Maciej, Jan Rybicki, and Mike Kestemont. ‘Stylometry with R: A Package for Computational Text Analysis’. The R Journal 8, no. 1 (August 2016): 107–21. https://doi.org/10/gghvwd.

El-Hadi, Mohamed M. Union List of Arabic Serials in the United States: The Arabic Serial Holdings of Seventeen Libraries. Occasional Papers 75. Urbana: University of Illinois, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 1965.

Flanders, Julia, and Fotis Jannidis, eds. The Shape of Data in Digital Humanities: Modeling Texts and Text-Based Resources. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315552941.

Gelvin, James L. ‘“Modernity”, “Tradition”, and the Battleground of Gender in Early 20th-Century Damascus’. Die Welt Des Islams 52, no. 1 (2012): 1–22. https://doi.org/10/ggwwhd.

Georgeon, François. ‘Changes of Time: An Aspect of Ottoman Modernization’. New Perspectives on Turkey 44 (2011): 181–95. https://doi.org/10/ggwwhb.

Glaß, Dagmar. Der Muqtaṭaf und seine Öffentlichkeit. Aufklärung, Räsonnement und Meinungsstreit in der frühen arabischen Zeitschriftenkommunikation. 2 vols. Mitteilungen zur Sozial- und Kulturgeschichte der islamischen Welt 17. Würzburg: Ergon Verlag, 2004.

Gooding, Paul. Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age: ‘Search All About It’. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

Grallert, Till. ‘To Whom Belong the Streets? Property, Propriety, and Appropriation: The Production of Public Space in Late Ottoman Damascus, 1875-1914’. FU Berlin, 2014.

———. An open, collaborative, and scholarly digital edition of Jirjī Niqūlā Bāz’s monthly journal ‘al-Ḥasnāʾ’ (Beirut, 1909-11) (version 0.1). OpenArabicPE, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3556246.

———. ‘Open Arabic Periodical Editions: A Framework for Bootstrapped Digital Scholarly Editions Outside the Global North’. Accessed 7 October 2020. https://openarabicpe.github.io/.

Grallert, Till, and Patrick Funk. An open, collaborative, and scholarly digital edition of Anastās Mārī al-Karmalī’s monthly journal ‘Lughat al-ʿArab’ (Baghdad, 1911–14) (version 0.1). OpenArabicPE, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3514384.

Grallert, Till, Manzi Tanna Händel, Dimitar Dragnev, Klara Mayer, and Daniel Lloyd. An open, collaborative, and scholarly digital edition of Muḥammad Kurd ʿAlī’s monthly journal ‘al-Muqtabas’ (Cairo and Damascus, 1906-1917/18) (version 0.8). OpenArabicPE, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.597319.

Grallert, Till, Xaver Kretzschmar, Jakob Koppermann, and Talha Güzel. An open, collaborative, and scholarly digital edition of ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Iskandarānī’s monthly journal ‘al-Ḥaqāʾiq’ (Damascus, 1910–12) (version 0.3). OpenArabicPE, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1232016.

Hanley, Will. ‘Digital Egyptian Gazette’. Digital Egyptian Gazette, 2016–. https://dig-eg-gaz.github.io/.

Hanssen, Jens. Fin de Siècle Beirut: The Making of an Ottoman Provincial Capital. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005.

HathiTrust Digital Library. ‘HathiTrust Research Center Awards Three ACS Projects for 2020’. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.hathitrust.org/htrc-awards-three-acs-projects.

Hermann, Rainer. Kulturkrise und konservative Erneuerung: Muhammad Kurd ʿAlī (1876-1953) und das geistige Leben im Damaskus zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts. Heidelberger Orientalistische Studien 16. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1990.

Hopwood, Derek. Arabic Periodicals in Oxford: A Union List. Oxford: St. Antony’s College, 1970.

Horrocks, Clare. ‘Nineteenth-Century Journalism Online—the Market Versus Academia?’ Media History 20, no. 1 (2014): 21–33. https://doi.org/10/ggwwhk.

Hourani, Albert. Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age: 1798-1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Höpp, Gerhard. Arabische und islamische Periodika in Berlin und Brandenburg 1915 - 1945. Berlin: Verlag Das Arabische Buch, 1994.

Iḥdādan, Zāhir. Bībliyūghrāfiyā al-ṣiḥāfa al-Jazāʾiriyya. al-Jazāʾir: al-Muʾassasat al-Waṭaniyya li-l-Kitāb, 1984.

Ilyās, Jūzīf. Taṭawwur al-ṣiḥāfa al-Sūriyya fī miʾat ʿām: 1865-1965. 2 vols. Bayrūt: Dār al-Niḍāl, 1982.

Jajko, Edward A. ‘Cataloging of Middle Eastern Materials (Arabic, Persian, and Turkish)’. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 17, no. 1 (1993): 133–48. https://doi.org/10/bp3crw.

Jockers, Matthew. Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. Topics in the Digital Humanities. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Jundī, Muḥammad Salīm. Iṣlāḥ al-fāsid min lughat al-jarāʾid. [Dimashq]: Maṭbaʿat al-Taraqqī, 1925.

Kaḥḥāla, ʿUmar Riḍa. Muʿjam al-muʾallifīn: tarajim muṣannifi al-kutub al-ʿarabiyya. 15 vols. Dimashq: Maṭbaʿat al-Taraqqī, 1957.

Khūrī, Yūsuf Quzmā. Mudawwanat al-ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiya. Edited by ʿAlī Dhū al-Fiqār Shākir. Vol. 1: Miṣr. Bayrūt: Maʿhad al-Inmāʾ al-ʿArabī, 1985.

Khūrīya, Yūsif Q. al-Ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya fī Filasṭīn 1876-1948. Bayrūt: Muʾassasat al-Dirāsāt al-Filasṭīniyya, 1976.

Kiessling, Benjamin, Matthew Thomas Miller, Maxim Romanov, and Sarah Bowen Savant. ‘Important New Developments in Arabographic Optical Character Recognition (OCR)’. Al-ʿUṣūr Al-Wuṣṭā 25 (2017): 1–13. https://www.middleeastmedievalists.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/UW-25-Savant-et-al.pdf.

Koppel, Moshe, Jonathan Schler, and Shlomo Argamon. ‘Computational Methods in Authorship Attribution’. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60, no. 1 (2009): 9–26. https://doi.org/10/bnxj7s.

Kurd ʿAlī, Muḥammad. Khiṭaṭ al-Shām. Vol. 6. Dimashq: Maṭbaʿat al-Mufīd, 1928. http://www.archive.org/details/kutat_cham_06.

Laramée, François Dominic. ‘Introduction to Stylometry with Python’, 21 April 2018. https://doi.org/10.46430/phen0078.

Mansour, Nadirah, and Marwa Gadallah. ‘al-Iḥtiyāj li-l-wājihāt al-iliktrūniyya bi-l-lughat al-ʿArabiyya’. presented at the Digital Orientalisms Twitter Conference 2020 (#DOsTC2020), 20 June 2020. https://twitter.com/NAMansour26/status/1274361436215574529.

Matusiak, Krystyna, and Qasem Abu Harb. Digitizing the Historical Periodical Collection at the Al-Aqsa Mosque Library in East Jerusalem, 2009. http://eprints.rclis.org/20444/.

‘Maṭbūʿāt ḳānūnu’. In Düstūr, 1:395–403. Tertip II 1. Der-i Saʿādet: Maṭbaʿa-yi ʿOŝmaniye, 1913.

‘Maṭbūʿāt niẓāmnāmesi’. In Düstūr, 2:220–26. Tertip I 2. Der-i Saʿādet: Maṭbaʿa-yi ʿĀmire, 1872.

Märgner, Volker, and Haikal El Abed, eds. Guide to OCR for Arabic Scripts. London: Springer, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4072-6.

Mestyan, Adam, and Till Grallert. ‘Jara’id: A Chronology of Nineteenth Century Periodicals in Arabic (1800-1900). A Research Tool’, 2012–. https://projectjaraid.github.io.

Moretti, Franco. Distant Reading. London: Verso, 2013.

Muruwwa, Adīb. al-Ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya: nashʾatuhā wa taṭawwuruhā. Bayrūt: Dār Maktabat al-Ḥayyāt, 1961.

Mussell, James. The Nineteenth-Century Press in the Digital Age. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230365469.

Nicholson, Bob. ‘The Digital Turn: Exploring the Methodological Possibilities of Digital Newspaper Archives’. Media History 19, no. 1: Special Issue: Journalism and History: Dialogues (31 January 2013): 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2012.752963.

‘Personalia’. Journal of the American Oriental Society 40 (1920): 144.

Pierazzo, Elena. Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories, Models and Methods. London: Routledge, 2015.

Rifāʿī, Shams al-Dīn al-. Tārīkh al-ṣiḥāfa al-Sūriyya. 2 vols. al-Qāhira: Dār al-Maʿārif bi-Miṣr, 1969.

Risam, Roopika. New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7tq4hg.

Robertson, Stephen. ‘The Differences Between Digital Humanities and Digital History’. In Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. https://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/read/untitled/section/ed4a1145-7044-42e9-a898-5ff8691b6628.

Rose, Richard B. ‘The Ottoman Fiscal Calendar’. Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 25, no. 2 (1991): 157–67. https://doi.org/10/ggwwg9.

———. Dīwān al-Ruṣāfī. Edited by Muḥī al-Dīn al-Khayyāṭ and Muṣṭafā al-Ghalāyīnī. Bayrūt: al-Maktaba al-Ahliyya, 1910.

Sahle, Patrick. Digitale Editionsformen: Zum Umgang mit der Überlieferung unter den Bedingungen des Medienwandels. Schriften des Instituts für Dokumentologie und Editorik. Köln: Institut für Dokumentologie und Editorik (IDE), 2013. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hbz:38-50112.

Sarkīs, Yūsuf Ilyān. Muʿjam al-maṭbūʿat al-ʿArabiyya wa-l-muʿarraba. 2 vols. Miṣr: Maṭbaʿat Sarkīs, 1928. http://shamela.ws/index.php/book/1242.

Seikaly, Samir. ‘Damascene Intellectual Life in the Opening Years of the 20th Century: Muhammad Kurd ʿAli and Al-Muqtabas’. In Intellectual Life in the Arab East, 1890-1939, edited by Marwan Rafat Buheiry, 125–53. Beirut: American University Of Beirut, 1981.

Seydi, Masoumeh, and Maxim Romanov. ‘Al-Ṯurayyā Project’, 2013–. https://althurayya.github.io/.

Shaykhū, Luwīs. Tārīkh al-ādāb al-ʿArabiyya fī al-rubʿ al-awwal min al-qarn al-ʿishrīn. Bayrūt: Maṭbaʿat al-Ābāʾ al-Yasūʿiyīn, 1926. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015008612619.

Thomsen, P. ‘Verzeichnis der arabischen Zeitungen und Zeitschriften Palästinas’. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 35, no. 4 (1912): 211–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27929096.

Thylstrup, Nanna Bonde. The Politics of Mass Digitization. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2018.

Ṭarrāzī, Fīlīb dī. Tārīkh al-ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya: yaḥtawī ʿalā jamīʻ fahāris al-jarāʾid wa al-majallāt al-ʿarabiyya fī al-khāfiqīn mudh takwīn al-ṣiḥāfa al-ʿarabiyya ilā nihāyat ʿām 1929. Vol. 4. Bayrūt: al-Maṭbaʿa al-Amīrikāniyya, 1933. http://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/crjdfsp1.

———. Tārīkh al-ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya. 3 vols. Bayrūt: al-Maṭbaʿa al-Adabiyya, 1913–1914.

Uluengin, Mehmet Bengü. ‘Secularizing Anatolia Tick by Tick: Clock Towers in the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic’. International Journal of Middle East Studies 42, no. 1 (2010): 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743809990511.

Underwood, Ted. ‘A Genealogy of Distant Reading’. DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly 11, no. 2 (10 July 2017). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/2/000317/000317.html.

Weber, Stefan. Damascus: Ottoman Modernity and Urban Transformation, 1808-1918. Translated by Stephen Cox. Vol. I. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2009.

Wittern, Christian. ‘Beyond TEI: Returning the Text to the Reader’. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative 4: Selected Papers from the 2011 TEI Conference (March 2013). http://jtei.revues.org/691.

Wrisley, David Joseph, and Najla Jakas. ‘On Translating Voyant Tools into Arabic’, 9 June 2016. https://djwrisley.com/on-translating-voyant-tools-into-arabic/.

Wrisley, David Jospeh, and Najla Jarkass. ‘RTL Software Localization and Digital Humanities: The Case Study of Translating Voyant Tools into Arabic’. presented at the Digital Humanities Summer Institute: Right2Left Workshop, 8 June 2019.

Yalman, Ahmet Emin. ‘The Development of Modern Turkey as Measured by Its Press’. Columbia University, 1914.

Zachs, Fruma. ‘Debates on Women’s Suffrage in the Arab Press, 1890-1914’. Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Des Morgenlandes 108 (2018): 275–95.

Zemmin, Florian. ‘Modernity Without Society? Observations on the Term Mujtamaʿ in the Islamic Journal Al-Manār (Cairo, 1898–1940)’. Die Welt Des Islams 56, no. 2 (2016): 223–47. https://doi.org/10/ggwwhh.

———. ‘Validating Secularity in Islam: The Illustrative Case of the Sociological Muslim Intellectual Rafiq Al-’Azm (1865-1925)’. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 44, no. 3 (169) (2019): 74–100.

Ziriklī, Khayr al-Dīn. al-Aʿlām: Qāmūs tarājim li-ashhar al-rijāl wa-l-nisāʾ min al-ʿArab wa-l-mustaʿribīn wa-l-mustashriqīn. 4th ed. Vol. 7. 8 vol. Bayrūt: Dār al-ʿIlm li-l-Malāyīn, 1979.

———. al-Aʿlām: Qāmūs tarājim li-ashhar al-rijāl wa-l-nisāʾ min al-ʿArab wa-l-mustaʿribīn wa-l-mustashriqīn. 4th ed. 8 vols. Bayrūt: Dār al-ʿIlm li-l-Malāyīn, 1979.

C.f. Stephen Robertson, ‘The Differences Between Digital Humanities and Digital History’, in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, ed. Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2016); Arguing with Digital History working group, ‘Digital History and Argument’ (White paper, 13 November 2017), https://rrchnm.org/argument-white-paper/.↩︎

David M Berry and Anders Fagerjord, Digital Humanities: Knowledge and Critique in a Digital Age (Cambridge; Malden: Polity, 2017), 2.↩︎

Ahmet Emin Yalman, ‘The Development of Modern Turkey as Measured by Its Press’ (New York, Columbia University, 1914); Fīlīb dī Ṭarrāzī, Tārīkh al-ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya, 3 vols (Bayrūt: al-Maṭbaʿa al-Adabiyya, 1913–1914).↩︎

E.g. Muḥammad Salīm Jundī, Iṣlāḥ al-fāsid min lughat al-jarāʾid ([Dimashq]: Maṭbaʿat al-Taraqqī, 1925); Luwīs Shaykhū, Tārīkh al-ādāb al-ʿArabiyya fī al-rubʿ al-awwal min al-qarn al-ʿishrīn (Bayrūt: Maṭbaʿat al-Ābāʾ al-Yasūʿiyīn, 1926), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015008612619; Yūsuf Ilyān Sarkīs, Muʿjam al-maṭbūʿat al-ʿArabiyya wa-l-muʿarraba, 2 vols (Miṣr: Maṭbaʿat Sarkīs, 1928), http://shamela.ws/index.php/book/1242, Yūsuf Asʿad Dāghir, Maṣādir al-dirāsa al-adabiyya, 2 vols (Ṣaydā: al-Maṭbaʿa al-Mukhliṣiyya, 1950); Adīb Muruwwa, al-Ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya: nashʾatuhā wa taṭawwuruhā (Bayrūt: Dār Maktabat al-Ḥayyāt, 1961); Shams al-Dīn al-Rifāʿī, Tārīkh al-ṣiḥāfa al-Sūriyya, 2 vols (al-Qāhira: Dār al-Maʿārif bi-Miṣr, 1969); Yūsif Q. Khūrīya, al-Ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya fī Filasṭīn 1876-1948 (Bayrūt: Muʾassasat al-Dirāsāt al-Filasṭīniyya, 1976); Yūsuf Aḥmad Dāghir, Qāmūs al-ṣiḥāfa al-Lubnāniyya 1858-1974 (Bayrūt: al-Maktaba al-Sharqiyya al-Kubrā, 1978); Jūzīf Ilyās, Taṭawwur al-ṣiḥāfa al-Sūriyya fī miʾat ʿām: 1865-1965, 2 vols (Bayrūt: Dār al-Niḍāl, 1982).↩︎

Ami Ayalon, The Press in the Arab Middle East: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); ‘The Arab Discovery of America in the Nineteenth Century’, Middle Eastern Studies 20, no. 4 (1984): 5–17, https://doi.org/10/b9tmbm; ‘Semantics and the Modern History of Non-European Societies: Arab “Republics” as a Case Study’, The Historical Journal 28, no. 4 (1985): 821–34, https://doi.org/10/cfszw3; Language and Change in the Arab Middle East the Evolution of Modern Arabic Political Discourse (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987); ‘Sihafa: The Arab Experiment in Journalism’, Middle Eastern Studies 28, no. 2 (1992): 258–80, https://doi.org/10/fqwxp9; ‘Modern Texts and Their Readers in Late Ottoman Palestine’, Middle Eastern Studies 38, no. 4 (2002): 17–40, https://doi.org/10/c8sg6m; ‘From Fitna to Thawra’, Studia Islamica 66, no. 66 (January 1987): 145–74, https://doi.org/10/c77s26; ‘Private Publishing in the Naḥda’, International Journal of Middle East Studies 40, no. 4 (November 2008): 561–77, https://doi.org/10/d2vxjg.↩︎

Exceptions are Donald J. Cioeta, ‘Thamarāt Al-Funūn, Syria’s First Islamic Newspaper, 1875-1908’ (PhD Thesis, Chicago, University of Chicago, 1979); Dagmar Glaß, Der Muqtaṭaf und seine Öffentlichkeit. Aufklärung, Räsonnement und Meinungsstreit in der frühen arabischen Zeitschriftenkommunikation, 2 vols, Mitteilungen zur Sozial- und Kulturgeschichte der islamischen Welt 17 (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag, 2004).↩︎

Florian Zemmin, ‘Validating Secularity in Islam: The Illustrative Case of the Sociological Muslim Intellectual Rafiq Al-’Azm (1865-1925)’, Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 44, no. 3 (169) (2019): 81. In addition, al-ʿAẓm also published in al-Muqtabas, al-Ittiḥād al-ʿUthmānī and other periodicals.↩︎

Florian Zemmin, ‘Modernity Without Society? Observations on the Term Mujtamaʿ in the Islamic Journal Al-Manār (Cairo, 1898–1940)’, Die Welt Des Islams 56, no. 2 (2016): 232, https://doi.org/10/ggwwhh.↩︎

Zemmin, ‘Validating Secularity in Islam’, 76. A computational query on the same digital remediation available to Zemmin reveals that al-ʿAẓm authored only 13 out of more than 4.300 articles.↩︎

Fruma Zachs, ‘Debates on Women’s Suffrage in the Arab Press, 1890-1914’, Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Des Morgenlandes 108 (2018): 286.↩︎

C.f. Roopika Risam, New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7tq4hg; c.f. Paul Gooding, Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age: ‘Search All About It’ (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018), 149–57; Nanna Bonde Thylstrup, The Politics of Mass Digitization (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2018), 79–100.↩︎

I use “shadow libraries” as proposed by Thylstrup, The Politics of Mass Digitization, 79–100, 81. to describe mass digitisation efforts that “operate in the shadows of formal visibility and regulatory systems” and in order to avoid the term “pirate” with its colonial connotations.↩︎

Mohamed M El-Hadi, Union List of Arabic Serials in the United States: The Arabic Serial Holdings of Seventeen Libraries, Occasional Papers 75 (Urbana: University of Illinois, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 1965); Derek Hopwood, Arabic Periodicals in Oxford: A Union List (Oxford: St. Antony’s College, 1970); Mohammed M. Aman, Arab Periodicals and Serials: A Subject Bibliography, Garland Reference Library of Social Science (New York: Garland, 1979); Fred De Jong, ‘Arabic Periodicals Published in Syria Before 1946: The Holdings of Zahiriyya Library in Damascus’, Bibliotheca Orientalis 36 (1979): 292–300; Zāhir Iḥdādan, Bībliyūghrāfiyā al-ṣiḥāfa al-Jazāʾiriyya (al-Jazāʾir: al-Muʾassasat al-Waṭaniyya li-l-Kitāb, 1984); Yūsuf Quzmā Khūrī, Mudawwanat al-ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiya, ed. ʿAlī Dhū al-Fiqār Shākir, vol. 1: Miṣr (Bayrūt: Maʿhad al-Inmāʾ al-ʿArabī, 1985); Gerhard Höpp, Arabische und islamische Periodika in Berlin und Brandenburg 1915 - 1945 (Berlin: Verlag Das Arabische Buch, 1994); Touraj Atabaki and Solmaz Rustămova-Tohidi, Baku Documents: Union Catalogue of Persian, Azerbaijani, Ottoman Turkish and Arabic Serials and Newspapers in the Libraries of the Republic of Azerbaijan (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 1995). I am part of the endeavour to gather and openly share information on all holdings of nineteenth-century Arabic periodicals; Adam Mestyan and Till Grallert, ‘Jara’id: A Chronology of Nineteenth Century Periodicals in Arabic (1800-1900). A Research Tool’, 2012–, https://projectjaraid.github.io.↩︎

A map based on the results of this and a similar query to the Arabic Union Catalogue is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4154171.↩︎

Such as Cengage Gale, Hathitrust, the British Library’s “Endangered Archives Programme” (EAP), MenaDoc, “Jarāyid: Arabic newspaper archive of Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine”, the Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies or the Institut du Monde Arabe.↩︎

Such as Arshīf al-majallāt al-adabiyya wa-l-thaqāfiyya al-ʿarabiyya or al-Maktaba al-Shāmila, Mishkāt, Ṣayyid al-Fawāʾid or al-Waraq.↩︎

The almost hegemonic interface to digitised collections focusses on a Google-like search bar and makes browsing titles—the classic way of accessing periodicals—nigh impossible. The de-contextualising of strings of text from the page and the wider context of the periodical immanent to keyword search has been repeatedly criticised as inadequate for the study of periodicals; e.g. Laurel Brake, ‘The Longevity of “Ephemera”: Library Editions of Nineteenth-Century Periodicals and Newspapers’, Media History 18, no. 1 (2012): 17, https://doi.org/10/b7x6ps; Gooding, Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age, 12–13; Adrian Bingham, ‘“The Digitization of Newspaper Archives: Opportunities and Challenges for Historians”’, Twentieth Century British History 21, no. 2 (June 2010): 229–30, https://doi.org/10/fsqbgx.↩︎

One major, publicly-funded research project for HTR is Transkribus (https://transkribus.eu/).↩︎

Volker Märgner and Haikal El Abed, eds., Guide to OCR for Arabic Scripts (London: Springer, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4072-6. is still relevant for current platforms; see the Internet Archive’s claim that Arabic is “currently not OCRable”; e.g. https://archive.org/details/1_20191109_20191109_1843.↩︎

Benjamin Kiessling et al., ‘Important New Developments in Arabographic Optical Character Recognition (OCR)’, Al-ʿUṣūr Al-Wuṣṭā 25 (2017): 1–13, https://www.middleeastmedievalists.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/UW-25-Savant-et-al.pdf. The approaches of the Open Islamicate Texts Initiative Arabic-script OCR Catalyst Project (OpenITI AOCP) will eventually find their way into HathiTrust etc.; see ‘HathiTrust Research Center Awards Three ACS Projects for 2020’, HathiTrust Digital Library, accessed 7 July 2020, https://www.hathitrust.org/htrc-awards-three-acs-projects.↩︎

The validity of this statement, of course, depends on the purpose of digitisation. If one was, for instance, interested in distant reading approaches to large corpora, such as the temporal distribution of certain keywords during a long print run, this would allow not just for aggregation on the issue level but probably even periods of full months and more. In consequence, error margins of almost one fourth in both Character Error Rate (CER) and Word Error Rate (WER) become seemingly acceptable; e.g. Nello Cristianini, Thomas Lansdall-Welfare, and Gaetano Dato, ‘Large-Scale Content Analysis of Historical Newspapers in the Town of Gorizia 1873–1914’, Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 51, no. 3 (26 March 2018): 144, https://doi.org/10/ggqm97.↩︎

‘Early Arabic Printed Books from the British Library’, 16 September 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20190916173504/https://p-www.gale.com/primary-sources/early-arabic-printed-books-from-the-british-library↩︎

For the genealogy of large-scale literary history under the label “distant reading” see Ted Underwood, ‘A Genealogy of Distant Reading’, DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly 11, no. 2 (10 July 2017), http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/2/000317/000317.html. The most often referenced founding works are Franco Moretti, Distant Reading (London: Verso, 2013). (collection of reprinted essays), Matthew Jockers, Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History, Topics in the Digital Humanities (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013).↩︎

On modelling as fundamental component of scholarly editing and the “core of any critical and epistemological activity” see Elena Pierazzo, Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories, Models and Methods (London: Routledge, 2015), 37–64; Julia Flanders and Fotis Jannidis, eds., The Shape of Data in Digital Humanities: Modeling Texts and Text-Based Resources (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315552941.↩︎

Will Hanley, ‘Digital Egyptian Gazette’, Digital Egyptian Gazette, 2016–, https://dig-eg-gaz.github.io/↩︎

C.f. Nadirah Mansour and Marwa Gadallah, ‘al-Iḥtiyāj li-l-wājihāt al-iliktrūniyya bi-l-lughat al-ʿArabiyya’, https://twitter.com/NAMansour26/status/1274361436215574529; David Joseph Wrisley and Najla Jakas, ‘On Translating Voyant Tools into Arabic’, 9 June 2016, https://djwrisley.com/on-translating-voyant-tools-into-arabic/; David Jospeh Wrisley and Najla Jarkass, ‘RTL Software Localization and Digital Humanities: The Case Study of Translating Voyant Tools into Arabic’.↩︎

The US-based HathiTrust, for instance, does not provide public or open access to its collections even to materials in the public domain under extremely strict US copyright laws when users try to access them from outside the USA. On the issue of unequal access to digitised collections see Gooding, Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age, 145–70. and especially his Figure 6.1 showing global access (or lack thereof) to the British Library Nineteenth Century Newspapers.↩︎

For good overviews over digital (scholarly) editing see Patrick Sahle, Digitale Editionsformen: Zum Umgang mit der Überlieferung unter den Bedingungen des Medienwandels., Schriften des Instituts für Dokumentologie und Editorik (Köln: Institut für Dokumentologie und Editorik (IDE), 2013), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hbz:38-50112; Pierazzo, Digital Scholarly Editing; Matthew James Driscoll and Elena Pierazzo, eds., Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories and Practices (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2016), https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0095.↩︎

For an overview of calendars see Jean Deny, ‘L’adoption du calendrier grégorien en Turquie’, Revue du monde musulman 43 (1921): 46–52; Richard B Rose, ‘The Ottoman Fiscal Calendar’, Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 25, no. 2 (1991): 157–67, https://doi.org/10/ggwwg9; Edward A. Jajko, ‘Cataloging of Middle Eastern Materials (Arabic, Persian, and Turkish)’, Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 17, no. 1 (1993): 133–48, https://doi.org/10/bp3crw; François Georgeon, ‘Changes of Time: An Aspect of Ottoman Modernization’, New Perspectives on Turkey 44 (2011): 181–95, https://doi.org/10/ggwwhb; Till Grallert, ‘To Whom Belong the Streets? Property, Propriety, and Appropriation: The Production of Public Space in Late Ottoman Damascus, 1875-1914’ (Berlin, FU Berlin, 2014), 26–34.↩︎

A particularly crass example with four errors in a single dateline can be found in the masthead to al-Haqāʾiq 1(6).↩︎

al-Muqtabas, for instance, was severely lagging behind its publication schedule by summer 1909. No. 4(7) was scheduled for Rajab 1327 aH (July/August 1909) according to its masthead, but only published in the first week of April the following year; see Jarīdat al-Muqtabas, no. 338, 7 April 1910.↩︎

Both Weber and Hanssen, for instance, missed the fact that the birthday of Sultan

Consider, for instance, the family of XML technologies. According to the XPath specifications, the format-date() function supports a number calendars beyond the Gregorian standard, including the Islamic hijrī calendar, since version 2.0. However, the actual support for calendars and languages is implementation-dependent and Saxon, the main XSLT, XPath and XQuery processor, has not implemented any of these alternative calendars; see documentation for format-dateTime().↩︎

Such as MAchine-Readable Cataloging (MARC) and Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) standards. Both are maintained by the Network Development and MARC Standards Office of the Library of Congress (NDMSO). MARC can be serialised as XML but frequently isn’t. MODS, in contrast, is expressed in XML and more human-readable.↩︎

Technical information on the project is scarce and contradictory despite two publications by the project leaders; Qasem Abu Harb, ‘Digitisation of Islamic Manuscripts and Periodicals in Jerusalem and Acre’, in From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives Programme, ed. Maja Kominko (Open Book Publishers, 2015), 377–415, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.12; Krystyna Matusiak and Qasem Abu Harb, Digitizing the Historical Periodical Collection at the Al-Aqsa Mosque Library in East Jerusalem, 2009, http://eprints.rclis.org/20444/.↩︎

This is true for the web interface and the IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework) API. See https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP119-1-4-3.↩︎

Till Grallert, ‘Open Arabic Periodical Editions: A Framework for Bootstrapped Digital Scholarly Editions Outside the Global North’, accessed 7 October 2020, https://openarabicpe.github.io/↩︎

TEI XML is the quasi-standard of textual editing and required by funding bodies and repositories for long-term archiving; cf. , DFG-Praxisregeln ‘Digitalisierung’ (Bonn: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, 2016), http://www.dfg.de/formulare/12_151/12_151_de.pdf.↩︎

The website was previously hosted at archive.sakhrit.co.↩︎

In other instances, such as the journals Lughat al-ʿArab and al-Ustādh, al-Maktaba al-Shāmila did provide page breaks that correspond to a printed edition.↩︎

Such an approach was proposed by Christian Wittern, ‘Beyond TEI: Returning the Text to the Reader’, Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative 4: Selected Papers from the 2011 TEI Conference (March 2013), http://jtei.revues.org/691. It has recently seen a number of concurrent practical implementations such as project GITenberg led by Seth Woodworth or Jonathan Reeve’s Git-lit.↩︎

Till Grallert and Patrick Funk, An open, collaborative, and scholarly digital edition of Anastās Mārī al-Karmalī’s monthly journal ‘Lughat al-ʿArab’ (Baghdad, 1911–14), version 0.1, OpenArabicPE, 2019, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3514384; Till Grallert, An open, collaborative, and scholarly digital edition of Jirjī Niqūlā Bāz’s monthly journal ‘al-Ḥasnāʾ’ (Beirut, 1909-11), version 0.1, OpenArabicPE, 2019, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3556246; Till Grallert et al., An open, collaborative, and scholarly digital edition of Muḥammad Kurd ʿAlī’s monthly journal ‘al-Muqtabas’ (Cairo and Damascus, 1906-1917/18), version 0.8, OpenArabicPE, 2020, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.597319; Till Grallert et al., An open, collaborative, and scholarly digital edition of ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Iskandarānī’s monthly journal ‘al-Ḥaqāʾiq’ (Damascus, 1910–12), version 0.3, OpenArabicPE, 2020, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1232016↩︎

For studies assessing these corpora and the methodological implications see Brake, ‘The Longevity of “Ephemera”’; James Mussell, The Nineteenth-Century Press in the Digital Age (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230365469; Clare Horrocks, ‘Nineteenth-Century Journalism Online—the Market Versus Academia?’, Media History 20, no. 1 (2014): 21–33, https://doi.org/10/ggwwhk; Gooding, Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age; Bob Nicholson, ‘The Digital Turn: Exploring the Methodological Possibilities of Digital Newspaper Archives’, Media History 19, no. 1: Special Issue: Journalism and History: Dialogues (31 January 2013): 59–73, https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2012.752963.↩︎

Samir Seikaly, ‘Damascene Intellectual Life in the Opening Years of the 20th Century: Muhammad Kurd ʿAli and Al-Muqtabas’, in Intellectual Life in the Arab East, 1890-1939, ed. Marwan Rafat Buheiry (Beirut: American University Of Beirut, 1981), 128↩︎