draft 2023-04-04

licensed as http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/

In 2014, I had just finished my PhD on the history of the street in late Ottoman Damascus (1875–1914) and moved to Beirut for a new post-doctoral research project on the genealogy of food riots across the predominantly Arabic-speaking Eastern Mediterranean from the nineteenth century to the present (Grallert 2020). The main source for both projects were periodicals—tens of thousands of newspaper and magazine articles published in Arabic and Ottoman Turkish across the region. But despite their quotidian nature, their pivotal role for central cultural phenomena of the time as the region’s first mass medium, and ubiquitous references in scholarly literature, surprisingly little of substance is known about this medium in terms of individual publication histories, distribution channels, and audiences or the number and whereabouts of surviving copies. This is particularly true for periodicals published outside the centers of the press in Beirut and Cairo.1

The sheer size of the corpus and the focus on social history suggests we muster help of computational tools and networked infrastructures. Working with textual material in Arabic and in a region with severely limited access to utilities forces us to reckon with the linguistic imperialism (Phillipson 1997) of global networked knowledge production and the nitty-gritty details of the multi-layered digital divides embodied in the infrastructural underpinnings of modern scholarship.

This is not a theoretical essay on the politics of digitization as a continuation of much older politics of archives, preservation and reproduction of cultural heritage, and ultimately the politics of representation embodied in the question of who writes history and of whom (C.f. Zaagsma 2022; Thylstrup 2018; Risam 2019; Fiormonte 2021; Grallert 2022b, 2021). Instead, I focus on the practical consequences, the always concrete affordances these politics create for the digitization of a specific society’s cultural record.

The first part of this essay is concerned with creating the necessary knowledge about the history of the Arabic periodical press, its material artifacts, and existing digital remediations. It introduces catalogues as historical documents and the consequences of hegemonic technological infrastructures of the Global North for creating and recording knowledge about cultural artifacts and practices of societies in the Global South. Here, I use Arabic as a prime example how character encodings, rendering engines, and a complete lack of interest from market-dominating software vendors and platforms for one of the United Nations’ only six official languages with more than 420 million active speakers exercise epistemic violence (c.f. Fiormonte 2021). Finally, I discuss our project Jarāʾid (Arabic for “newspapers”),2 the design choices and our experiences in producing a crowd-sourced union list of all Arabic periodicals published worldwide until 1929.

The second part turns to making cultural artifacts accessible to human readers and computational methods. I briefly introduce existing digital artifacts as being limited by the state of OCR-technologies and fractured data silos, paywalls, and geofencing before turning to our project Open Arabic Periodical Editions (OpenArabicPE)3 as a practical critique of infrastructures of exclusion.

The two projects featured in this essay were heavily influenced by Alex Gil’s advocacy for minimal computing approaches, whom I met at Digital Humanities Institute – Beirut 2015 and later that year at DHSI while teaching introductory courses to TEI. Both projects responded to the work of ADHO’s Global Outlook::Digital Humanities special interest group (GO::DH) and minimal computing as structured around the balancing “what do we need?” with “what do we have?” (Gil and Ortega 2016; Risam and Gil 2022, emphasis mine). Jarāʾid and OpenArabicPE address two interconnected needs of marginal scholarly communities with a simple idea: Creatively repurpose existing open data, tools, and infrastructures in order to provide sustainable public and free access to reliable knowledge about periodicals as well as high-quality digital editions and to do so not just in Latinized transcriptions as is established scholarly practice in the Global North but in their original script and languages. Both projects can be considered fairly successful attempts at applying a minimal computingapproach to address our severely limited resources. Jarāʾid currently holds information on 3550 periodical titles, including holding-information on 775 titles in 233 library collections and links to 233 at least partially digitized titles. OpenArabicPE provides a corpus of openly accessible digital scholarly editions of six journals published between 1892 and 1918 in Baghdad, Beirut, Cairo, and Damascus with a total of 41 volumes, 645 individual issues, and more than 6 million words.

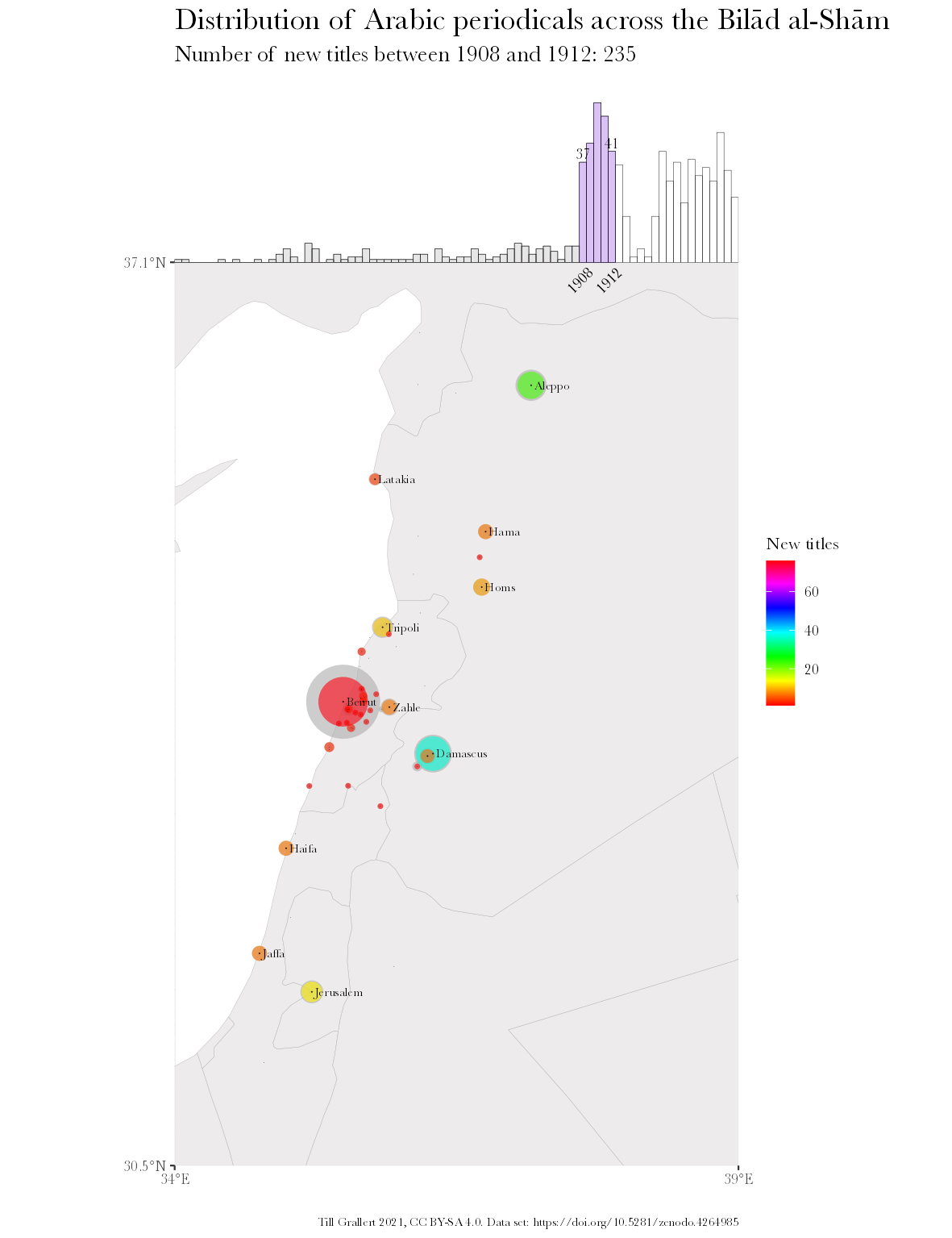

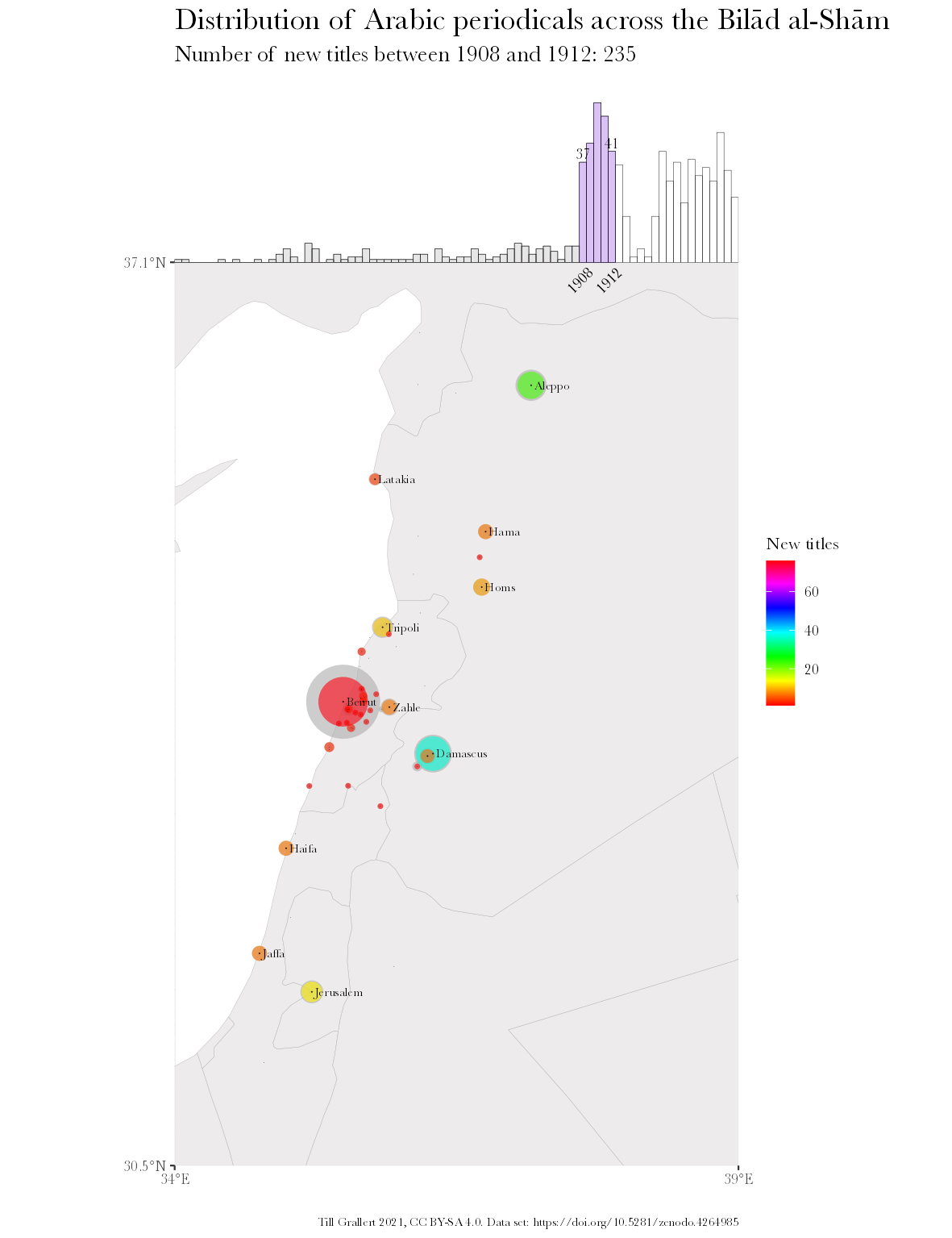

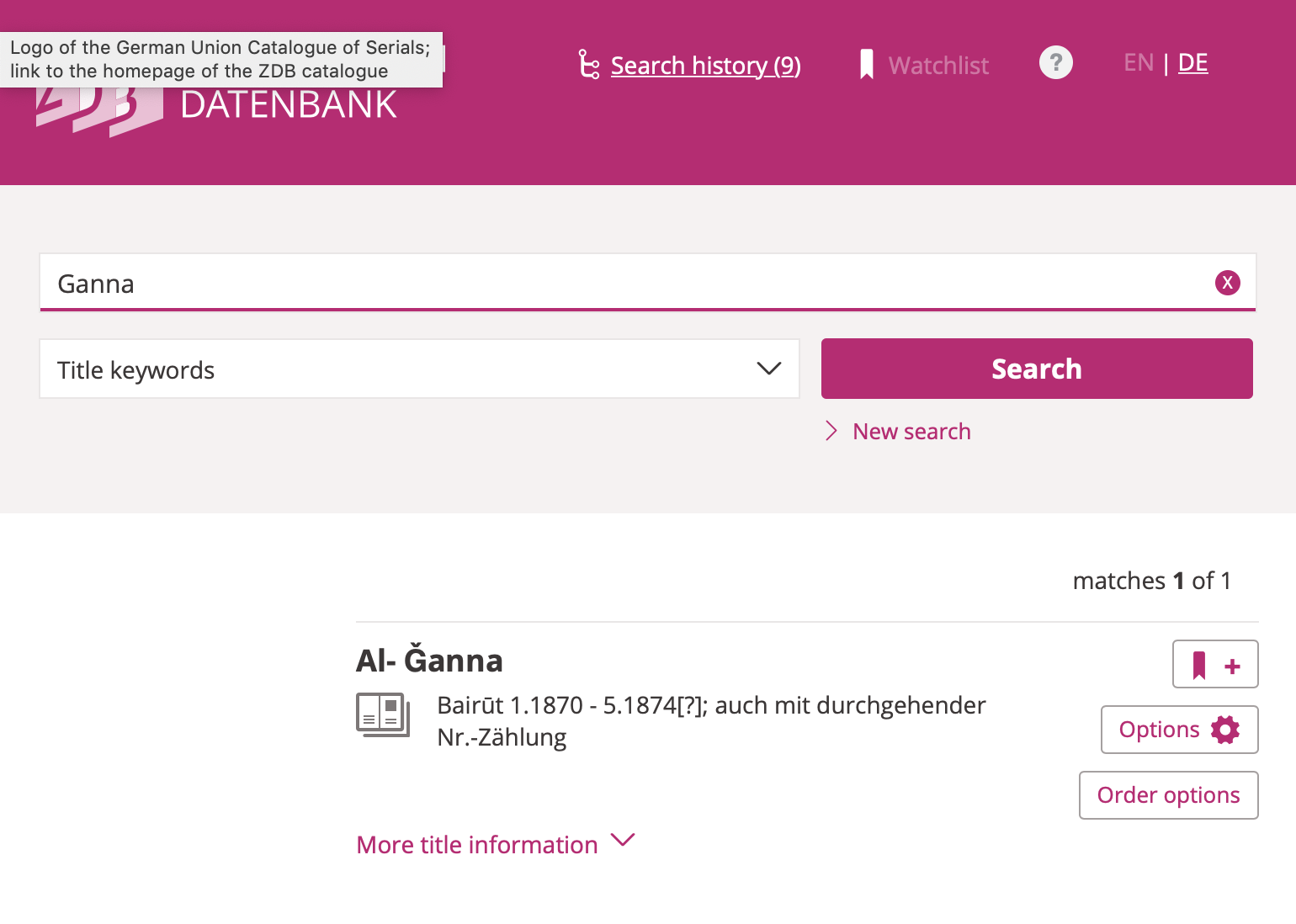

Commencing with the question “What do we need?” as scholarly communities concerned with the historical societies of the Eastern Mediterranean of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, our first need, was (and still is) to improve our knowledge about periodicals as the embodiment of socio-economic relations, intellectual traditions, and political frameworks, their manifestation in a limited number of material artifacts, the transmission of individual artifacts into private and public collections, and finally their occasional digital remediation. In order to investigate the extent of food riots across cities of the Syrian hinterland in summer 1910 (C.f. Grallert 2020), one would need to know which papers, if at all, were published in Hama, Homs, Gaza or Nablus and therefore potentially printed eye-witness accounts (fig. 1 presents such information based on our cataloguing project introduced below). One would then need to establish if copies survived the turmoil that wreaked havoc upon the region and its cultural record over the last century, where to find surviving copies, and how to access them.

At this point we have to acknowledge that digitization is inseparable from multi-layered digital divides—a chicken-egg problem of interwoven knowledge systems, representations, and socio-technical infrastructures that is difficult to tease apart.

Despite quotidian impressions to the contrary, many library catalogues have not been digitized or published online. This is particularly true for institutions outside the Global North and collections of material from the Global South. The Lebanese National Library, for instance, was closed over night in 1975 and its collections, including extensive periodical collections, were hastily stuffed into boxes and stored in the port of Beirut. There they remained for the next forty-odd years. A rehabilitation project has been under way since 2003 and reading rooms were opened to the public in 2018. However, the catalogue is still advertised as forthcoming (“The Lebanese National Library” 2015). Manually compiled union catalogues are a Herculean task and have largely fallen out of fashion with the advent of Online Public Access Catalogues (OAPC). Given their publication dates and the necessary time for information collection, printed union catalogues should probably be read as historical sources rather than finding aids (E.g. El-Hadi 1965; Hopwood 1970; Aman 1979; De Jong 1979; Iḥdādan 1984; Khūrī 1985; Höpp 1994; Atabaki and Rustămova-Tohidi 1995). Likewise, library catalogues are layered historical documents that accumulate traces of their socio-technic affordances with each remediation. Looking at any one of the many entries for ʿAbdallāh Nadīm al-Idrīsī’s weekly journal al-Ustādh, published in Cairo from 1892 to 1893, in Worldcat,4 we most likely will not encounter a record newly created from the material artifact by an expert cataloguer with domain knowledge in Arabic periodicals and the ability to read Arabic script. Even if so, she will most likely have had to contend with technological systems ill-suited, if not unable, to deal with the metadata in its original script, calendars or naming conventions.

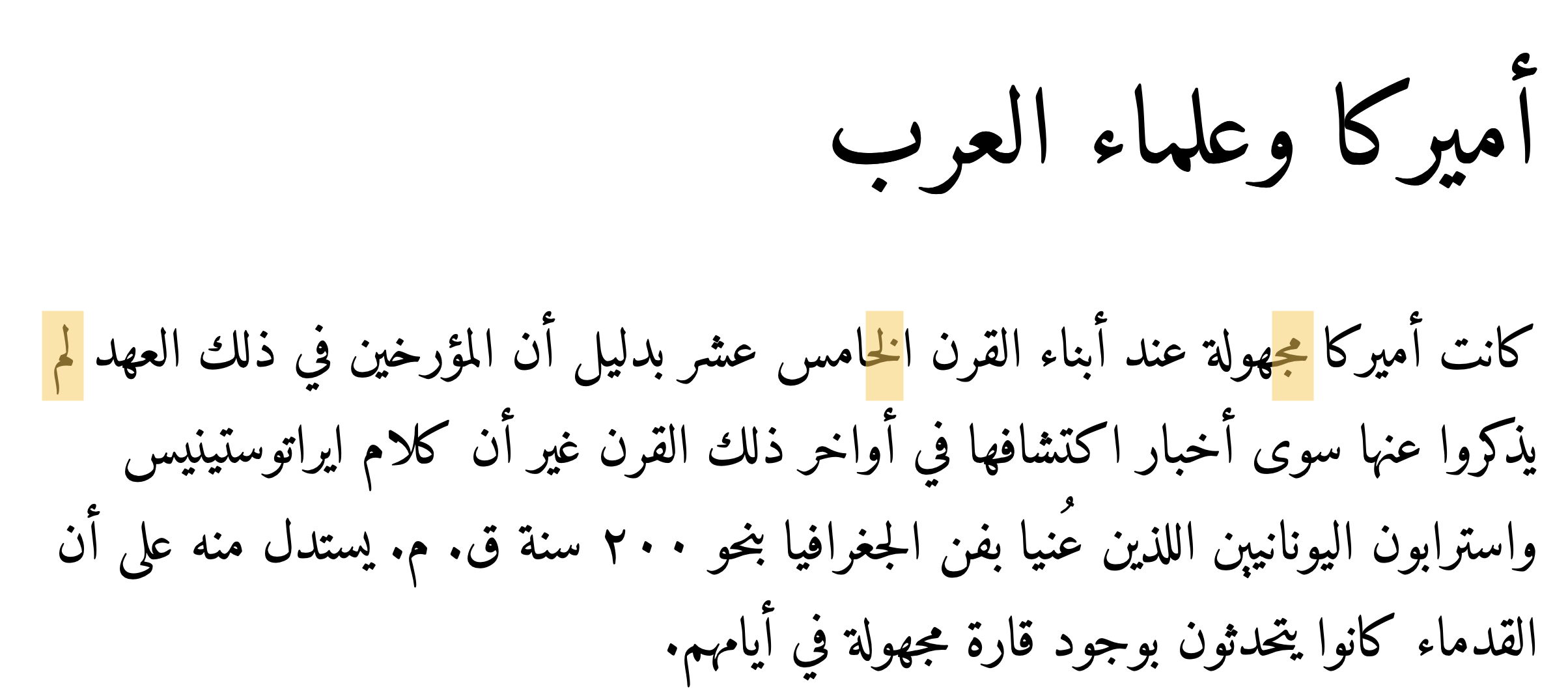

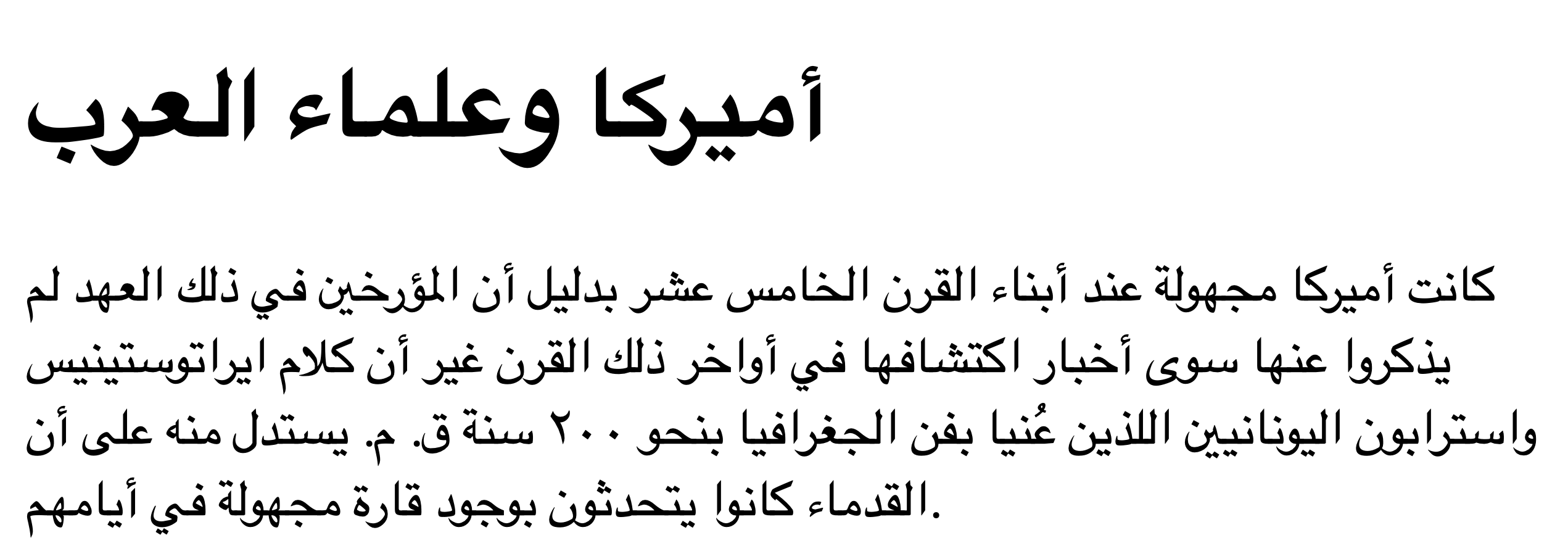

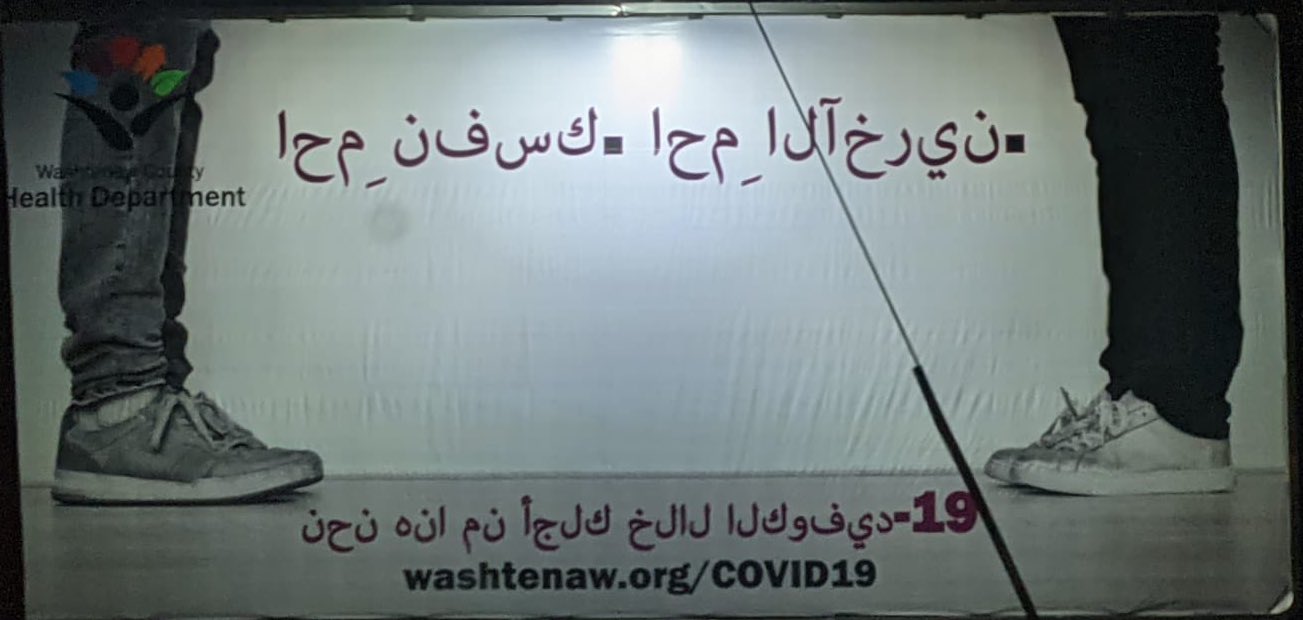

Arabic is one of the main historical and living human languages. It is one of only six official languages of the United Nations with more than 420 million active speakers and the ritual language of approximately 1.9 billion Muslims or one quarter of the world’s population. Arabic is also the third most important script after Latin and Chinese and a writing system for many historic and contemporary Asian and African languages, such as Persian, Urdu, Pashtu, Ottoman, Uzbek or Uighur (Mumin and Versteegh 2014). The script is written from right to left, most letters connect in the writing direction within a word, and letters have up to four letterforms depending on their position within a string. Multiple letters share the same basic letterform (rasm). Diacritical signs (iʿjām), mostly dots below and above the rasm, allow to decrease semantic ambiguity. Depending on writing style and typefonts, multiple letterforms will form ligatures. Letterforms and ligatures will not necessarily sit on a single baseline and baselines can be tilted (fig. 2). There are only few exceptions to these script-specific writing rules across languages. Importantly for us, the diacritics are not strictly necessary for readers as is evidenced by recent efforts at circumventing surveillance and censorship of authoritarian Arab regimes by using (an approximation of) the rasm on social media (see fig. 3 for an example). Furthermore, their use is subject to changing cultural preferences. Some regional practices all but omit them from specific letters, particularly at the end of a word.5

![Pseudo-rasm of the text in fig. 2. Automatically generated with Pohl ([2020] 2022).](../assets/images/arabic_rasm.png)

Type-written card-catalogues, hot-metal printing presses, electronic computers (understood as an interdependent combination of hardware and software) form a global hegemonic technology stack bound up in historically contingent cultural traditions of the Global North. Mechanically and, later, electronically recording information in scripts other than Latin—particularly complex scripts with a much larger number of graphemes and different writing directions—was never considered sufficiently important or profitable to be supported out-of-the-box (Nemeth 2018; Singh 2018). Computational systems not only derive from their type-setting ancestors and enforce Latin script grammar upon other writing systems, they also inherited the concept of national languages and do not consequently distinguish between scripts and languages. The character-encoding standard Unicode enabled vendor-independent exchange and interoperability of texts in Arabic script but it continues to adhere to the script grammar of Latin and the affordances of movable type-printing and does not support the Arabic system of basic letterforms (c.f. Fiormonte et al. 2015, 3–4).6 Unicode’s organizing principle of code points is a confusing combination of scripts and languages that results in multiple code points for the same glyph. Anybody entering Arabic texts into a computer has to select one specific interpretation, one and only one Unicode representation of a textual string they want to encode. They have to either normalize historical or geographic orthographic variance or pick visually-matching but technically “wrong” glyphs. The resulting large variety of encodings for the same string of Arabic letterforms depends largely on the language of operating systems and keyboard settings on the input device (c.f. Veisi, MohammadAmini, and Hosseini 2020). Egyptian cultural preferences, for instance, would virtually always omit the two dots underneath a final yāʾ (U+064A: ي). To mirror such cultural preferences, one can either select the Arabic alif maqṣūra (U+0649: ى) or the Persian ye (U+06CC: ی) (c.f. Taghi-Zadeh et al. 2017). Unfortunately, search algorithms built into modern operating systems are not aware of these variances and any application software relying on them will return skewed results without additional efforts at regularization or a reduction to the rasm (Milo and Martínez 2019). This is illustrated by the first letter of the text body of fig. 2 and fig. 3. Even though they look identical, searching the test file for ك will reveal that they have different unicode codepoints.7

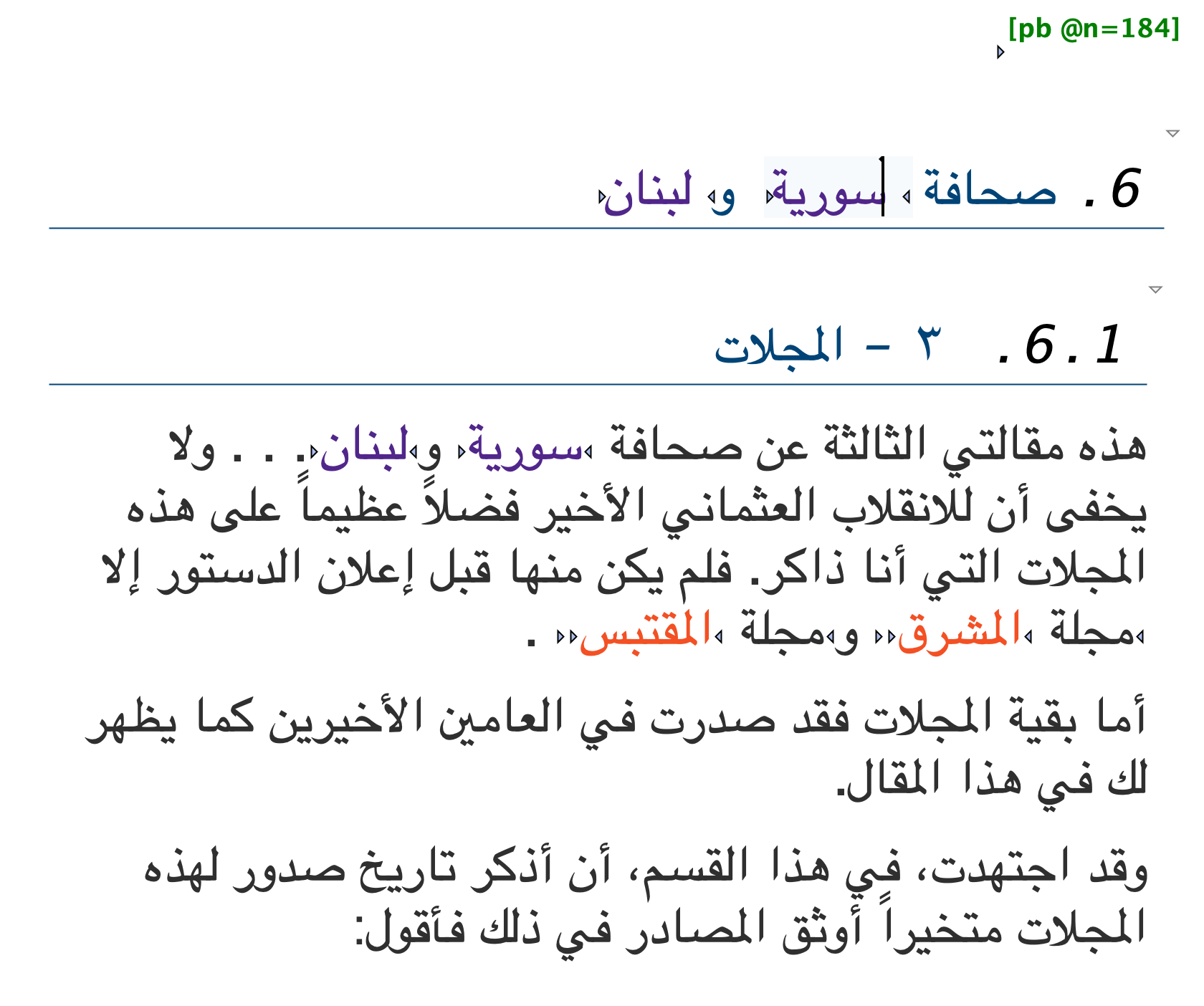

The necessary human-machine interfaces for interacting with textual

information present another layer of inaccessibility for those wanting

to engage with Arabic text as character encoding and rendering are two

different steps. Support for the correct rendering of Arabic as

right-aligned and with letters connecting from right to left is growing

but remains hit-and-miss depending on operating systems and software

applications—even on the web. HTML5 (Hypertext

Markup Language) is the current standard for structuring and

presenting content on the World Wide Web. It is maintained as a “living

standard” by the Web Hypertext Application

Technology Working Group (WHATWG), whose members are the

leading vendors of web browsers: Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Mozilla.

Most importantly for our discussion, HTML5 added the global

@lang attribute, which mirrors the earlier

@xml:lang attribute for explicitly specifying the language

of a document or parts thereof through the use of BCP 47

language tags, such as “ar” for Arabic or “en” for English (Network Working Group 2009).

Yet, despite having been originally developed in 2008 and being

maintained by an industry consortium of leading browser vendors, no

major modern web browser, however, uses the @lang attribute

in their built-in CSS for text-alignment or font

selection. Even if a website declares its content as being written in

Arabic, web browsers, such as Chrome, Firefox or Safari, do not

correctly render the text as right-aligned (fig. 4). The necessary fix

requires only a single line of code

(*[lang="ar"] {direction:rtl;})—from everyone publishing

text in right-to-left scripts on the Web. The problem is not purely

aesthetic. Trailing punctuation marks, for instance, become leading

punctuation marks without these adjustments (Final line on fig. 4).

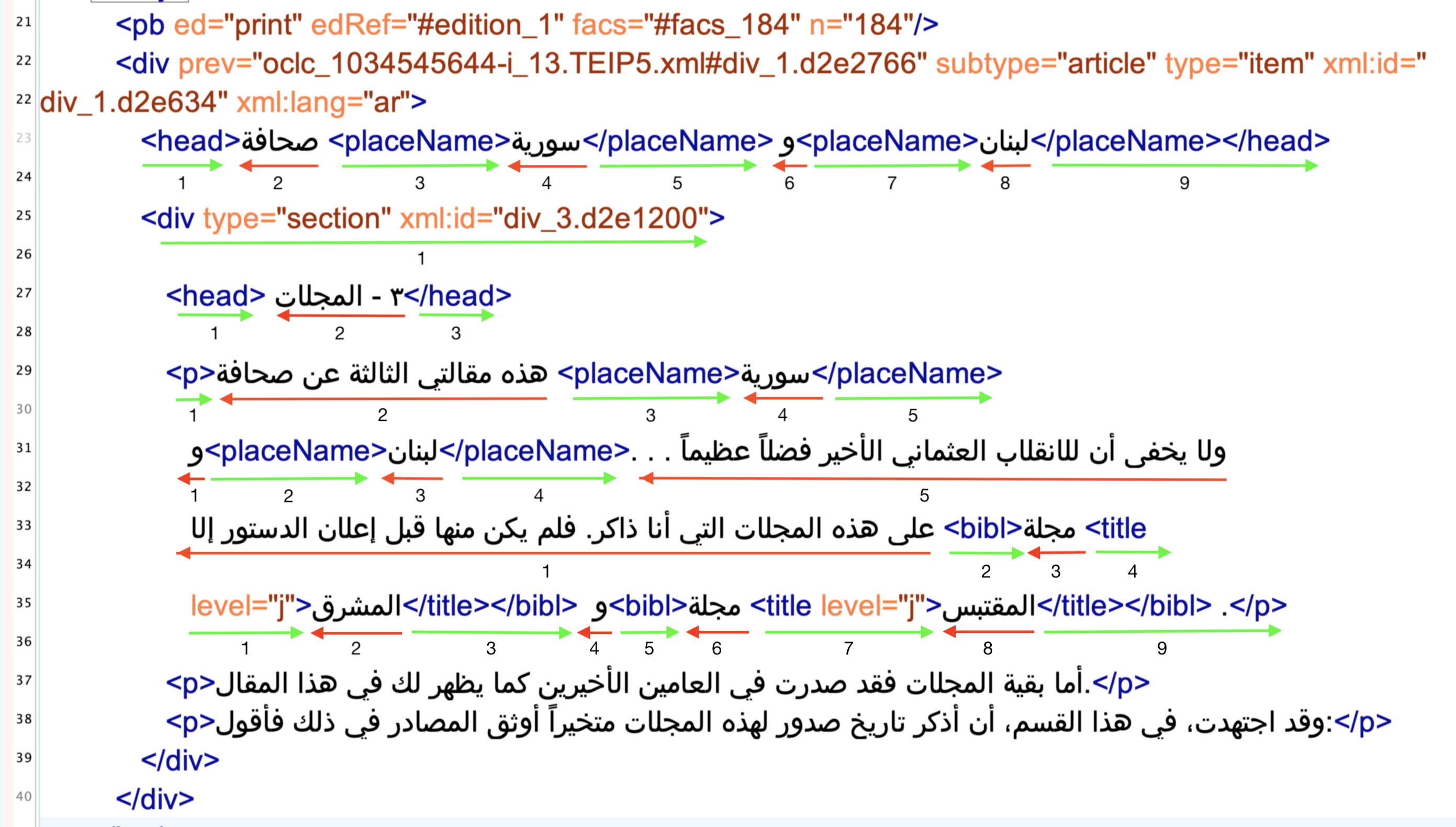

Software for editing digital editions marked up in Extensible Markup Language (XML) following the guidelines of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) (TEI Consortium 2020) represent the same attitude in their CSS to render a more human-friendly view of the commonly verbose XML files. The developers of the popular oXygen XML editor added the relevant CSS for rendering TEI/XML in their “author mode” in 2015 (v17, see fig. 7) and in response to our feature request. But this support for correctly rendering Arabic and some other RTL languages is limited to TEI/XML.

Needing to interact with Arabic content instead of merely reading it

or purely accessing it computationally, leads to another major issue in

the insufficient support for Arabic in the digital realm: the display of

bi-directional text on a two-dimensional surface (as opposed to the

logical character sequence, which is a one-dimensional string). If we

assume writing directions differ in one dimension, such as left-to-right

and right-to-left, it is impossible to visually decide whether both

scripts are of equal importance to the text or whether and which one

takes precedence over the other (fig. 6). Algorithms and standards solve

this problem through two approaches: either assume Latin as the implicit

paradigm, ignore the possibility of other directions, and render

everything from left to right (fig. 5) or look at the first proper

letter in the logical document order. Unicode follows the second

approach. XML, for example, is fully

unicode-compliant and supports tag and attribute names in any script as

long as they can be encoded in unicode, even thought this is almost

never implemented in practice. However, the XML declaration

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> at the very

beginning of the file needs to be written in Latin script. According to

the unicode bidirectional (bidi) algorithm, this establishes

left-to-right as the base direction and

causes all computational tools to assume that they encounter a document

with a left-to-right reading order and leads to the aforementioned

misalignment of punctuation marks (Ishida 2016;

“BiDi Algorithm” 2021).

Beyond the fundamental impossibility to adequately record written Arabic in digital form, the cultural record and practices of societies from the Global South require constant efforts of translation and transcription, themselves intrinsically entangled with the socio-technical traditions of the Global North (C.f. Dugan and Montpellier 2021). The journal al-Ustādh is a simple, yet powerful example. “al-Ustādh” is, a transliteration of the Arabic title الاستاذ into Latin script following the widely adopted system of the International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES), as is the rendering of the publisher’s name عبد الله النديم الإدريسي as ʿAbdallah al-Nadim al-Idrisi (note that IJMES does not use diacritics for personal names). Catalogers in German-speaking countries would follow a system with a 1:1 character transliterations devised by the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (DMG) and record the title as al-Ustāḏ. In addition to the output language, transcription schemes differ between input languages in the same script. The British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP), for instance, misread the Ottoman Turkish title يكي تصوير افكر as تصوير افكر , assumed it was Arabic (because Ottoman was written in Arabic script until 1924) and “correctly” transcribed it as Taṣwīr Afkār while the correct transcription of the Ottoman would have been Yeni Taṣvīr-i Efkār (British Library n.d.). Finally, such transcription schemes require diacritics not necessarily available on technical systems and not commonly recognized by the OCR-algorithms used for retro digitization of card catalogues.

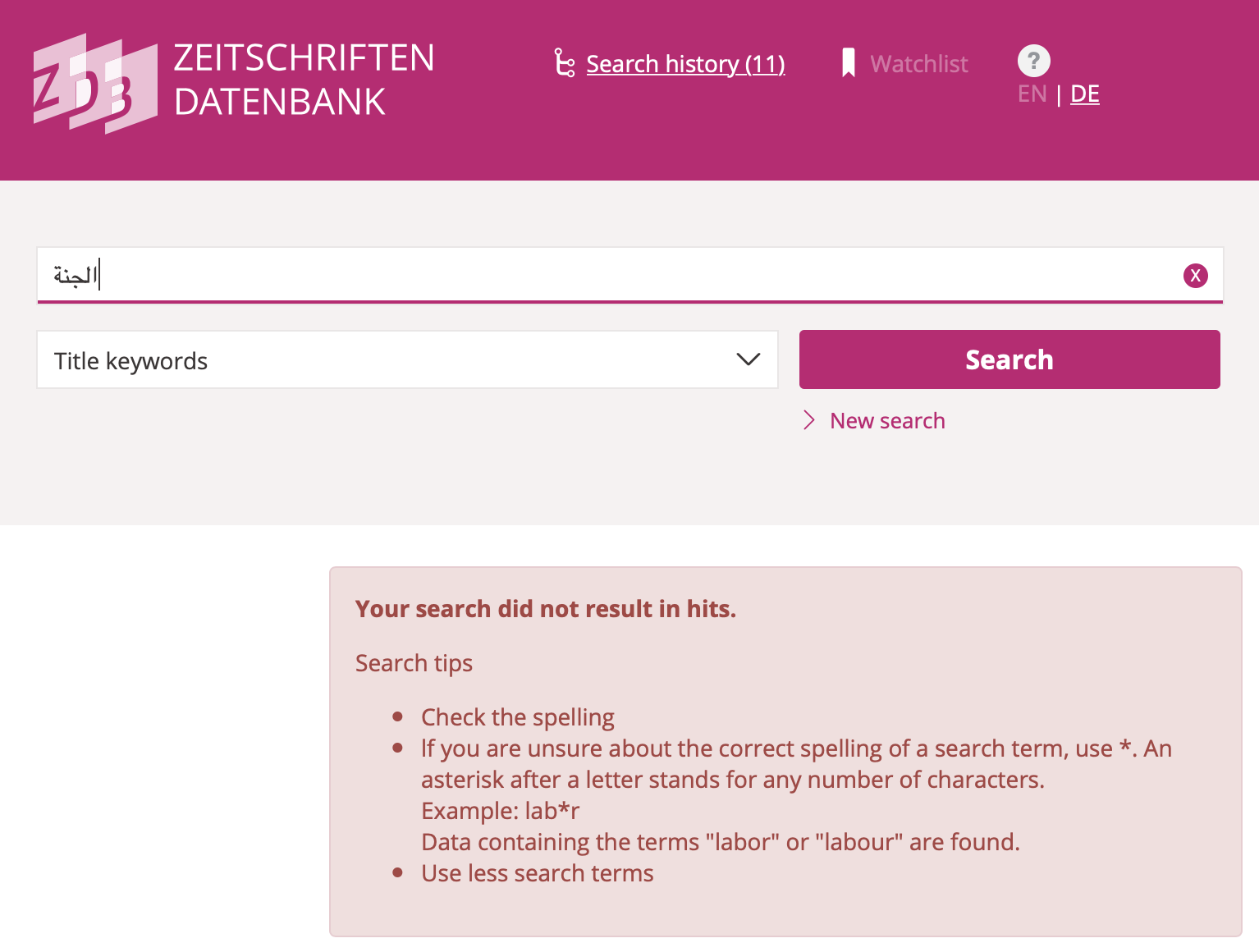

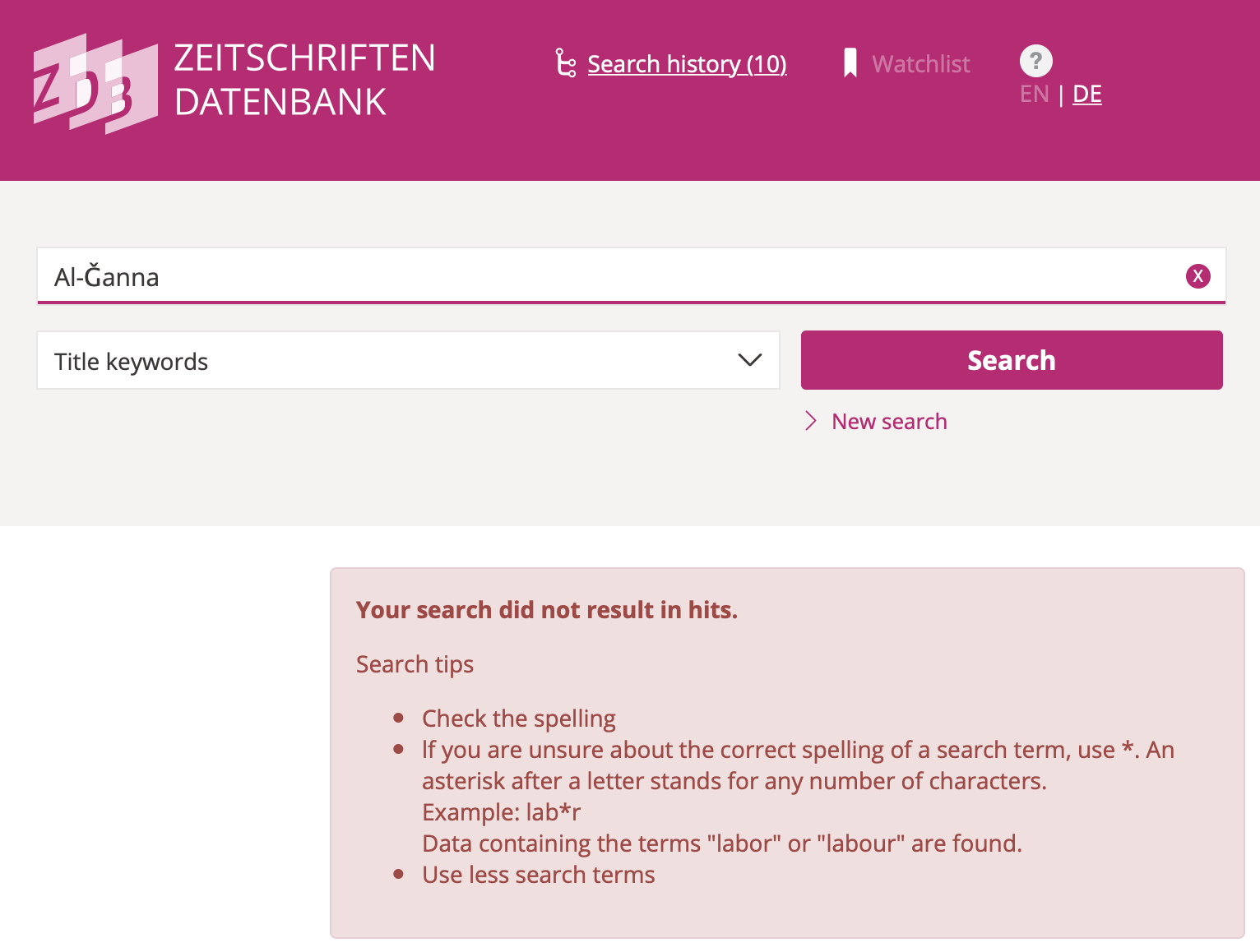

Discovery systems across the board are unsuited for this plurality of scripts and the large variety of transcriptions. All come with idiosyncrasies of their own. Many apparently aim at normalizing all Latin-script queries to ASCII by substituting all letters with diacritics, French accents, German Umlaute etc. with the English “base” letter. Worse, these choices are rarely documented and communicated to their users. Through ignorance or lack of interest in providing potentially costly services to communities outside the Global North and their cultural record, users are commonly left to their own tools. They have to try every version of a string they can think of and know how to enter them into the machine (see figs. 8-10).

The project “Jarāʾid: A Chronology of Arabic Periodicals (1800-1929)” has seen many iterations since its inception by Adam Mestyan in the early 2010s (Mestyan, Grallert, and et al. 2020; Mestyan and Grallert 2012–2015, 2020). At its core, Jarāʾid is a volunteer effort of scholars working with periodicals to openly share their collective knowledge about the publication history of Arabic periodical titles and their surviving copies, including digitised artefacts. I have been involved in the project as one of its main contributors and lead on data modelling and some iterations of the website since 2012. Starting from a modest table of a few hundred titles in a Word document, Jarāʾid has grown into a catalogue of more than 3200 Arabic periodicals from all around the globe, recording inter alia known titles, editors, publishers, places of publication, dates of first issue, and additional publication languages in case of multilingual publications. Rooted in the scholarly practices described above, information was originally gathered in Latinized transcriptions as found in sources and library catalogues and then normalized into the IJMES system. In recent years, we have computationally re-transcribed these Latin transcriptions into Arabic script based on heuristic approaches of rules and look-up tables. Jarāʾid therefore represents not just the only comprehensive union list of this material but the only one that can be searched and browsed in the original script. Finally, I have integrated holding information from HathiTrust, the Zeitschriften Datenbank (ZDB), a database of periodical holdings in German-speaking countries, and the library of the American University of Beirut based on public APIs (former two) and personal collaborations (the latter) (Grallert 2022a).

Jarāʾid is a very modest effort but it has become indispensable to the field despite our failure to attract any funding beyond an initial sum of 500 Euros. Even though the project predates the enunciation of minimal computing by GO::DH (Gil and Ortega 2016; Risam and Gil 2022) it resonates with the questions and approaches outlined therein: focus on the things we can do and build the infrastructures we need “without the help we can’t get” (Gil and Ortega 2016, 29). Our technical decisions, from data formats to software stacks, resulted from balancing our scholarly need as a community with the limited knowledge, tools, and infrastructures at our disposal. TEI/XML is certainly not what one would expect for bibliographic metadata but XML and related technologies was the only data serialization format we had experiences with. In addition, the pilot for what later became FIHRIST had just adapted TEI/XML to be a viable format for catalogues of Arabic manuscripts (C.f. Soualah and Hassoun 2012; Ortolja-Baird et al. 2019, 3). TEI/XML also allowed us to treat bibliographic data as a historical source and to annotate it with information on the origin of information, certainty of stated facts, dates, and links to external authority files in a semantically rich catalogue without a relational database. The resulting data—mainly TEI/XML files and their derivates—are hosted on GitHub. Releases are archived in the publicly-funded European research data repository Zenodo. Jarāʾid thus satisfies our goals of accessibility, sustainability, and credibility.

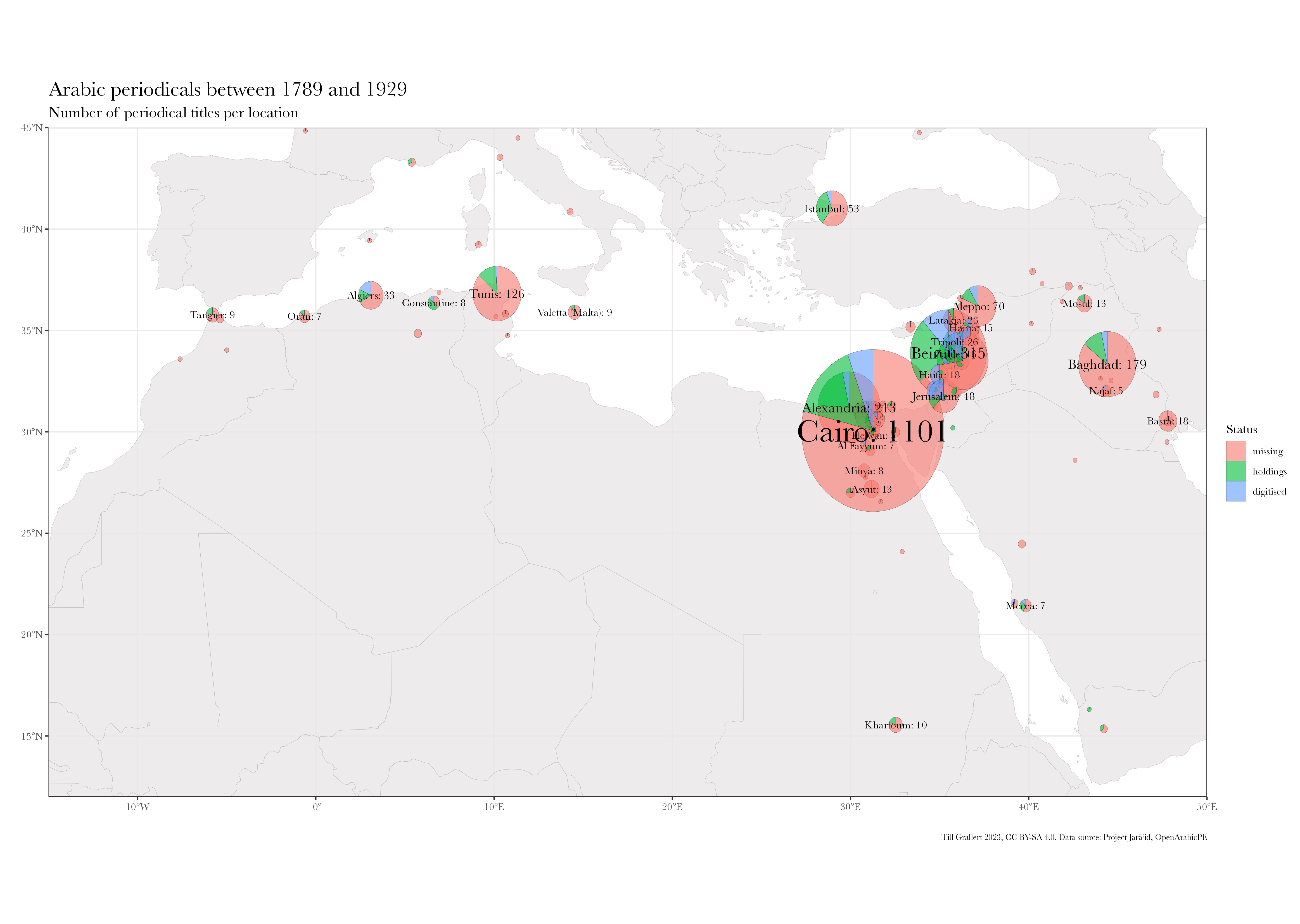

Based on the Jarāʾid dataset, we can now address some of the questions outlined in the introduction. fig. 11 shows the distribution of all Arabic periodical titles published across South West Asia and North Africa (SWANA) between 1789 and 1929. It also provides information on the ratio of titles with known holdings and digital remediations. fig. 12 shows the 775 or 21,83% of all 3550 titles in the dataset that could be located in collections. Almost one third of them, 233 or 6.56% of all titles, have digital remediations. While the digitization quote of titles in collections is surprisingly high, it must be kept in mind that we cannot resolve information on the extent of digitization. Even if only a single issue was digitized, the periodical title will be included in this count. The Jarāʾid dataset also provides an astonishing insight in the uncoordinated nature of scanning efforts. 66 periodicals or 28,33% have been digitized by multiple institutions and 21 of this subset by three and more. Considering the limited resources and relatively high cost of digitization, it would surely make sense if future efforts where directed towards those titles not yet digitized at all.

The very limited extent of digitization is at least partially explained by the knowledge gap and interrelated survival and collection biases. Here, we are interested in the meaning of digitized. The vast majority of those 233 periodicals is solely available as digital facsimiles due to the challenges Arabic script poses to traditional, segmentation-based approaches to computational text recognition. Accuracy rates for leading Arabic OCR solutions are well below 75% on the character level (Alghamdi and Teahan 2017; Alkhateeb, Abu Doush, and Albsoul 2017; cf. Märgner and El Abed 2012; Habash 2010), which causes the Internet Archive to state that the “language [is] not currently OCRable” (item description for Kurd ʿAlī 1923). Commercial vendors frequently make opaque claims of highly accurate text recognition technologies but none share their code or data for evaluation. Their search-centric interfaces return high numbers of false positives. With the extent of false negatives—strings not found even though they are present in the original—impossible to determine, such data layers are nigh impossible to use beyond anecdotal evidence (Grallert 2022b, sec. 13; 2021, 64–65).

OCR technologies for non-Latin scripts and ligatures such as Arabic have seen vast improvements with the widespread application of machine-learning approaches—from Kraken, to Transkribus and Tesseract—which generally have shown to reliably produce high levels of accuracy independent of input language and script (Kiessling et al. 2017).8 They still suffer, however, from insufficient recognition of layouts and reading orders and the lack of models trained for this specific genre of texts. 9 Most of the material currently available online has been digitized over the course of the last twenty years and would require renewed effort and substantial funding to apply the latest OCR technologies.10

Digitized should also not be conflated with being openly accessible on the internet. As Tim Sherratt (2019) called on us to query for the meaning of access, one has to ask “access to what and for whom?”. Many digitized Arabic periodicals are kept in data silos with no application programming interfaces (APIs) or the option to manually download more than individual page images. They are protected from their readers by layers of paywalls, geofencing, and forced personal registration. al-Muqtabas, for example, is commonly deemed in the public domain by vendors in the United States. Copies from the University of Minnesota and Princeton University are openly available online through HathiTrust—for scholars at member institutions and the general public in the US as determined by a user’s IP address. Everyone else will see blank pages or needs access to VPN services. Automated downloads frequently violate terms of use even if the vendor designates the material as being in the public domain. In one instance, such attempts resulted in a (temporary) blanket block of our home institution’s entire IP range. Such one-time downloads in order to peruse collections locally are relevant insofar as repeatedly loading a large number of high-resolution images is unnecessarily taxing for expensive or low-bandwidth internet connections.

In consequence, we witness a neo-colonial absence of the Global South from the digital cultural record (Risam 2019; c.f. Gooding [2017] 2018, 149–57; Thylstrup 2018, 79–100). The shocking differences are probably best illustrated by the comparison of the number of digitized Arabic periodicals with digitized newspapers from the German state of Hesse (tbl. 1) (“1914-1918: Der Erste Weltkrieg im Spiegel hessischer Regionalzeitungen” 2019).

| Arabic periodicals (1798–1918) | WWI as mirrored by Hessian regional papers | |

|---|---|---|

| community | c. 420 million Arabic speakers | c. 6.2 million inhabitants |

| periodicals | 2054 newspapers and journals | 125 newspapers |

| digitized | 156 periodicals | 125 newspapers with more than 1.5 million pages |

| type | mostly facsimiles | facsimiles and full text |

| access | paywalls, geo-fencing | open access |

| interface | mostly foreign languages only | local and foreign languages |

Open Arabic Periodical Editions (OpenArabicPE, 2015–) is a project to design and implement workflows for sustainable digital scholarly editions (DSE) with the affordances of the Global South. Based on the guiding principles of accessibility, simplicity, sustainability, and credibility, OpenArabicPE unites openly available digital facsimiles from institutional scanning efforts with human-transcribed text from shadow libraries and models them in TEI/XML as an open, standard-compliant, and well-established format for digital editions.

al-Maktaba al-shāmila (The Comprehensive Library, 2005–, henceforth Shamela) is the largest of a number of extremely popular shadow libraries for Arabic texts (Verkinderen 2020).11 Shamela is widely used but rarely cited by scholars (Grallert 2022b, sec. 30; c.f. Miller, Romanov, and Savant 2018, 104) and has been repeatedly employed for building scholarly corpora with a focus on distant reading approaches to classical texts (Belinkov et al. 2016; Alrabiah, Al-Salman, and Atwell 2013; Gundelfinger and Verkinderen 2020; “OpenITI Documentation” n.d.). OpenArabicPE was the first project to emphasise the transformation of material from Shamela into verified scholarly editions and remains the only one with a modern focus. OpenArabicPE is built onto a number of (as it turned out) manual transcriptions of Arabic periodicals from late 19th and early 20th centuries, which were added to Shamela in the first half of 2010. The motivation, funding, and people behind this project remain unclear and no additional periodicals from that period have been added to Shamela since.

OpenArabicPE aims at providing a means to verify transcriptions against facsimiles and thus to generate the necessary ground truth for training text recognition algorithms, a reliable corpus for distant reading, and reliably citable digital remediations. Despite our extremely limited resources—no project funds, no staff beyond volunteering interns, and no equipment beyond our own computers—we have published a corpus of six periodical editions with a total of 41 volumes, 645 issues and more than six million words (tbl. 2). All files, including bibliographic metadata on the article level in a number of standard formats, are published on GitHub, which also hosts a static webview for human readers based on the TEI Boilerplate, which had to be adapted for left-to-right scripts. Releases are archived in the Zenodo research data repository.12 Our plan to provide stable access through Canonical Texts Services (CTS) and integration into CLARIN‘s Virtual Language Observatory was abandoned after an initial upload of all issues of al-Muqtabas because of unsustainable maintenance costs and our editions’ evolving character.13

| Periodical | Place | Publisher | Dates14 | DOI | Volumes | Issues | Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| al-Ḥaqāʾiq | Damascus | ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Iskandarānī | 1910–13 | 10.5281/zenodo.1232016 | 3 | 35 | 298090 |

| al-Manār 15 | Cairo | Muḥammad Rashīd Riḍā | 1898–1918 | 20 | 387 | c.3000000 | |

| al-Muqtabas | Cairo, Damascus | Muḥammad Kurd ʿAlī | 1906–18 | 10.5281/zenodo.597319 | 9 | 96 | 1981081 |

| al-Ustādh | Cairo | ʿAbdallāh Nadīm al-Idrīsī | 1892–93 | 10.5281/zenodo.3581028 | 1 | 42 | 221447 |

| al-Zuhūr | Cairo | Anṭūn al-Jumayyil | 1910–13 | 10.5281/zenodo.3580606 | 4 | 39 | 292333 |

| Lughat al-ʿArab | Baghdad | Anastās Mārī al-Karmalī | 1911–14 | 10.5281/zenodo.3514384 | 3 | 34 | 373832 |

| total | 41 | 645 | c.6166783 |

We designed and applied workflows to automatically transform EPub files

(which are largely zipped folders of HTML) from Shamela into TEI/XML.

Part of this step was to normalise the variety of unicode code points

and to extract as much structural mark-up as possible from the HTML

source. We modelled each issue as a single TEI/XML file in order to keep

the original organisation of texts in this compound medium as they were

published. Remediations of the material into other organisational

structures for editing or reading purposes are left to future

developments and user input. The individual periodical issue also

happened to be the only reliable structural information provided by

Shamela. Individual

files provided structural information in various forms, from structural

(e.g. <span class="title">) to stylistic tags

(<span class="red">) but only very little proved

reliable enough for automatic conversion. For example, Shamela somewhat

consistently recorded all first-level articles and sections but no news

items and articles within sections and no sections within longer

articles for the journal al-Muqtabas. Thus, structural

information for items in the “News and ideas” (akhbār wa

afkār) section, such as (al-Muqtabas

1911), were not recorded (see fig. 13). The same is true for

explicit authorship information in bylines. We tried to catch both

phenomena in multiple iterations of our conversion processes based on

the length of paragraphs (<p>) and their position

within the surrounding text string: Short paragraphs in predefined

sections were assumed to signify the beginning of constituent articles.

Short paragraphs at the end of articles were presumably bylines.

This approach depends on reliable and consistent transcription of paragraphs and we learned that this had not been the case for all journals available from Shamela. Consistency and reliability also differed between issues of the same journal, probably indicating different human transcribers and editors. Algorithmic searches for uncharacteristically short pages with close reading of these pages substantiated the hypothesis of human transcribers because most omissions can be plausibly explained by common human errors: skipping a few words on a long line, jumping a small number of lines, or turning two pages at once. This also indicates that Shamela did not implement quality control mechanisms, such as double-keying, for its transcription process. Finally, we incidentally found unmarked comments interspersed in the transcription itself, stating, for example, that someone could not read the following four lines in the copy in front of them (al-Sharīf 1911, 422). From these notes, common orthographic normalization, and the omission of all words in Latin script, we can safely deduce that the transcribers were Arabic speakers. We are still looking for ways to adequately acknowledge their work beyond a generic reference in the metadata section of our TEI/XML files.

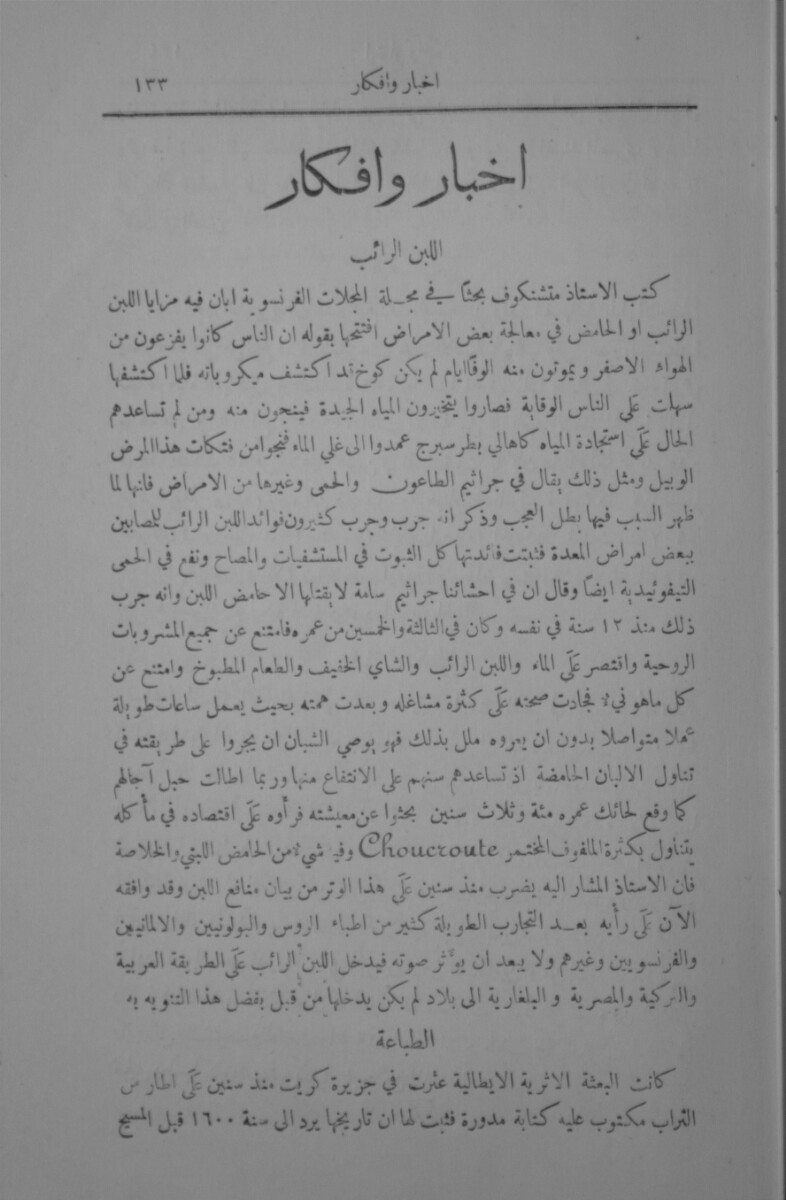

Adding and validating structural information required to identify the

corresponding digital facsimile or material artefact, which means

identifying the page the digital text was transcribed from. Arabic

journals and magazines were organised into annual, numbered volumes and

numbered issues corresponding to the their respective publication

schedule (monthly, fortnightly, weekly etc.). Unlike newspapers,

journals restarted their issue count with every volume. Shamela’s

transcriptions, on the other hand, abolished volumes as organising

principle and counted (available) issues in a consecutive sequence (see

the sidebar in fig. 13, which identifies the issue as number 61 instead

of number 2 of volume 6).

Locating the corresponding issue therefore required knowledge about

every periodical’s actual publication schedule. This could usually only

be established by accessing physical copies or digital facsimiles

because journals frequently diverted from their official publication

schedule by publishing fewer issues per volume.16

Shamela‘s human-readable dating information at the beginning of each issue proved largely fictional both in regards to a journal’s official publication schedule and individual issues’ actual publication dates. Our process for generating the necessary bibliographic metadata for linking digital texts to facsimiles was a hybrid one: automatic iteration based on known publication dates and validation against the original.

Digital facsimiles are available from a growing number of vendors. The British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) published the scans of Arabic periodical collections held by the al-Aqṣā Mosque’s library in Jerusalem (EAP119) in the early 2010s, which included the two Damascene periodicals that had just been transcribed by Shamela.17 We have since also added links to facsimiles from HathiTrust, Translatio, and Arshīf al-majallāt al-adabiyya wa-l-thaqāfiyya al-ʿarabiyya (The Archive of Arabic Literary and Cultural Magazines), the largest Arabic platform for facsimiles of historical periodicals. With regard to the latter, one must note that proclaimed facsimiles cannot be taken as such prima facie. As it turned out, they had rendered the text of an entire volume of al-Muqtabas from Shamela in a original-looking layout and served them as “fakesimiles” (Grallert 2022b, sec. 14). This further emphasises the need for and the value of vetted text and image layers in digital scholarly editions, such as the ones produced by OpenArabicPE.

Ultimately, locating page breaks in the text stream in order to link them to digital facsimiles proved to be the most labour-intensive task. Recording the original position of page breaks had apparently not been a priority for Shamela’s anonymous transcribers. While some periodicals faithfully followed the original, others did not and introduced their own page breaks. fig. 13 and fig. 14 demonstrate this mismatch. While Shamela recorded the page number as 45 (fig. 13), digital facsimiles from EAP show the article was published on page 133 (fig. 14). Consequently, every one of the c.8000 page breaks in the journals al-Muqtabas and al-Ḥaqāʾiq needed to be manually marked up by volunteers.18 My gratitude goes to Dimitar Dragnev, Talha Güzel, Dilan Hatun, Hans Magne Jaatun, Xaver Kretzschmar, Daniel Lloyd, Klara Mayer, Tobias Sick, Manzi Tanna-Händel and Layla Youssef, who contributed their time to this task.

On the technical level, linking is trivial, particularly with the increasing adoption of IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework) infrastructures in GLAM institutions. Links to externally hosted facsimiles, on the other hand, are the most volatile component of our data layer and we already encountered three major instances of link rot. Two were caused by vendors moving servers and changing protocols: The British Library moved EAP to IIIF in 2017 and Arshīf al-majallāt al-adabiyya wa-l-thaqāfiyya al-ʿarabiyya moved to a new domain in 2019. HathiTrust, on the other hand, removed the facsimiles of Princeton’s copy of al-Haqāʾiq 1 (1910) from the public domain without any explanation in 2016 and only reinstated public access six years later after multiple inquiries. Such link rot inevitably requires a lot of manual labour to figure out the patterns in new URLs (if any) and to write the necessary scripts to update all TEI files.

This paper introduced some of the very practical difficulties of digitising the cultural record of societies of the Global South, namely the predominantly Arabic-speaking communities and multilingual societies of the Eastern Mediterranean. Venturing into the basics of character encoding and rendering, library catalogues and discovery systems, and ultimately mass-digitisation and their genealogies as rooted in the physical and epistemic violence of colonial regimes and hierarchies of power between the Global North and South, I posed that despite having inherently fewer resources at their disposal, those concerned with digitising the Arabic textual cultural record have to constantly negotiate tools and infrastructures ill-suited, if not openly hostile to this task. Turning to minimal computing as a way to tactically address the needs of our scholarly communities with the means and embodied knowledge at hand,

Two projects

Open ends:

Jarāʾid needs to move towards integrating as much as possible into Wikidata. OpenArabicPE led to me getting a MSCA PF, which aimed at using the data for analysis and as ground truth for ML-based HTR. However, due the precariousness of the academic job market dominated by outrageously short fixed-term contracts, I returned the grant funding when I got a much longer, albeit still fixed-term contract in a grant-funded infrastructure project.

For a detailed overview of the state of Arab Periodical Studies see (Grallert 2021).↩︎

Available online at https://projectjaraid.github.io and https://github.com/projectjaraid.↩︎

Available online at https://openarabicpe.github.io and https://github.com/openarabicpe. See also Grallert (2022b).↩︎

For examples see https://www.worldcat.org/title/41055160 or https://www.worldcat.org/title/644003547.↩︎

For an introduction to the particularities of Arabic script see Nemeth (2017, 14–22); Gruendler (n.d.); Bauer (1996); Milo (2011).↩︎

On the background of Unicode and its application to Arabic see Nemeth (2017, 400–406); Milo (n.d.). Nemeth provides the most concise overview of the work of Thomas Milo, the most profound critic of digital approaches to Arabic script and the founder of DecoType (2017, 410–34).↩︎

The file is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7781543.↩︎

Some projects working on languages that have seen script reforms in the twentieth century, such as Turkish, directly transcribe Arabic into Latin script with HTR (Kirmizialtin and Wrisley 2022).↩︎

The “Open Islamicate Texts Initiative Arabic-script OCR Catalyst Project” (OpenITI ACOP) will train models for the most frequent fonts and types (Open Islamicate Texts Initiative (OpenITI) 2019) and their technology will eventually find its way into HathiTrust (“HathiTrust Research Center Awards Three ACS Projects for 2020” 2020).↩︎

On the environmental cost of machine learning see Alkaoud and Syed (2020, 124); Strubell, Ganesh, and McCallum (2019); Baillot et al. (2021).↩︎

Others are Mishkāt, Ṣayyid al-Fawāʾid or al-Waraq.↩︎

For a detailed project description see Grallert (2022b).↩︎

(Grallert et al. 2017). The endpoint at http://cts.informatik.uni-leipzig.de/muqtabas/cts/ is still functional as of January 2023.↩︎

The current cut-off date is 1918.↩︎

Since Riḍā’s Tafsīr, which accounts for about one fifth of al-Manār’s content, was not included Shamela’s transcription, it is also missing from the digital edition. See Zemmin (2016, 232).↩︎

Technical information on the project is scarce and contradictory despite two publications by the project leaders; Abu Harb (2015); Matusiak and Abu Harb (2009).↩︎

In other instances, such as the journals Lughat al-ʿArab and al-Ustādh, Shamela did provide page breaks that correspond to a printed edition.↩︎